Share buy backs have supported markets and these were at historic highs in 2013

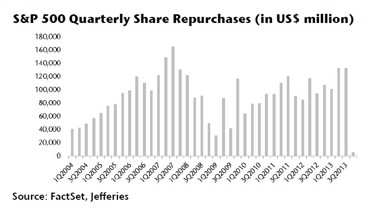

Share buybacks have been the rage on Wall Street for some years now. But 2013 was clearly a year where the numbers have swelled to titanic proportions. Eerily, the only period in the last ten years that these have been higher was towards the end of 2007. The S&P and global markets registered multi-year bull market peaks before they crashed in a heap as the global financial crises overwhelmed them.

As we move into 2014, there are many who wonder if all this money buying back their own shares is well spent or are corporates, in their zeal to deliver stock returns, throwing good money behind their over-valued stocks and investors simply cheering them on, so long as stock prices are rising.

Take a look at how large these numbers have become.

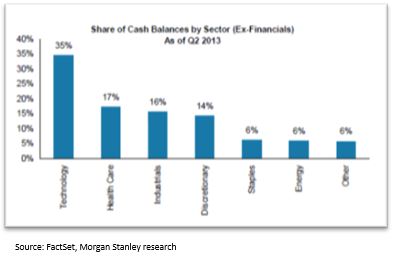

FactSet data reveals that companies in the S&P500 bought back US$123.9bn of stock in 3QCY13, adding up to US$448.1bn in the last twelve months. The IT sector accounted for nearly a quarter of this figure in 3QCY13.

At the same time, within the S&P500, a mere sixteen companies failed to either pay a dividend or affect a share buyback during the past one year.

Buy backs create discrepancies – they hide growth and reduce free float.

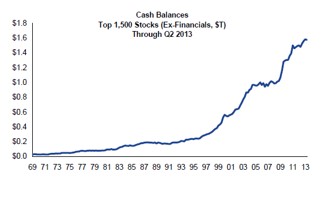

Companies can return surplus cash to shareholders through dividends and/or share buybacks for the most part. We find that a large number of companies deliver EPS growth over time, engineered in large part through hefty buybacks of their own stocks. These buybacks are often the larger of the components of cash pay-outs, the other being dividends. While a part of the argument could be that it is more tax-efficient, it makes less sense when the same managements are seen to be borrowing for effective buybacks and paying out dividends. A classic outcome of ultra-low interest rates surely.

Another unintentional consequence of buying back shares in large quantities over years is a material shrinkage in share capital, often far more than what ESOPs can possibly compensate. As a result, a reduction in the free-float and the dilution of existing shareholders over time provide other reasons for some classes of shareholders to be aggrieved.

Yet this strategy has kept all concerned in a happy position. Shareholders are only too pleased to receive more cash in their hands and see their stock values and wealth rise. Under-performing companies have been spared the wrath of otherwise declining stock values as earnings growth remained anaemic in this period. Company boards have been gleeful in gloating over the total stock returns delivered by their company annually to shareholders and thereby extended their stay in several boardrooms across corporate America.

However, buy backs at high prices will be questioned

As we move into 2014, we are certain that several investors and shareholders are going to ask uncomfortable questions of managements about the wisdom of buying back stock at ‘any price’ as they seem to be doing right now. What is the optimum price level at which they consider a share buyback is EPS or value accretive to shareholders? Would they not be better off just paying the cash out as special dividends and leave the choice of reinvesting the cash in their companies to shareholders themselves? Why do they not plough the cash back into the business directly or acquire competitors or expand into new frontiers? Could they not spend more on R&D and innovation? Most corporates today do not seem prepared to come up with answers to many of these questions.

The worst are the “borrow to buy back” group

As stock prices rise, a company can buy back less number of shares for the same sum of money and effectively make it less EPS productive. Some companies regularly borrow to meet the shortfall in cash required to sustain share buybacks. This has been justified by the cheap and easy money available today. As a result debt levels are creeping up in companies.

Stocks which have rallied, supported primarily by such purchases and dividend yield support, risk a debacle at some stage if their underlying profit growth is insufficient to support current valuations. If interest rates start going back up sooner than expected, then interest costs would eat into cash flows leaving even less to be distributed.

This support for the market could wane

Corporate ‘taper’ could become the next new subject of debate with investors in the year ahead. The asset allocation choices that managements make in future are likely to come under greater scrutiny. We believe that the time is not too far when managements will need to take a fresh look at share buybacks. A buy back slow down however need not be viewed negatively so long as the cash is well spent to grow the business and profits. It would mean though, in the short to medium term, that stock returns would have to be driven increasingly through organic profit growth rather than by engineering EPS growth through financial creativity.

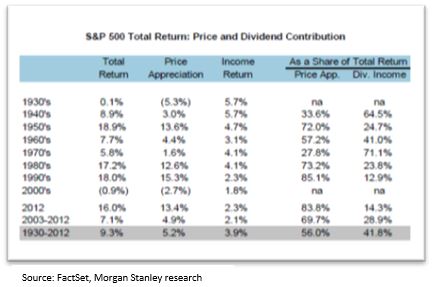

Research by Morgan Stanley in a note in November 2013 makes for interesting reading (see chart on the left). It says that since 1930, dividends have accounted for over 40% of total returns for investors in S&P500 companies. However that figure was 29% for the period 2003-2012 and just 14.3% in 2012 alone.

This should not be surprising given the strong and almost incessant rise in stock prices in the U.S. in the past two years. Considering where share prices reside now, it is more than likely that dividend pay-outs could rise further from here as the efficacy of share buybacks begins to wane and their wisdom is challenged.

The end of corporate buy backs (the taper of corporate buy backs) is not necessarily bad – the cash could be used for productive investments

Some of the anguish regarding the probably or impending corporate ‘taper’ is perhaps misplaced. Corporate ‘taper’ of share buybacks, if it were to happen, may not be such a bad thing after all. It could reduce the arguable misallocation of cash and lead to a more productive use of it. In either case, so long as it leads to earnings growing organically, there would be little to complain. Corporates could and would, if the economy picks up steam, plough cash back into the business through higher allocations to R&D and new product innovation and development, acquisitions, expansions into new markets or simply pay it out in the form of special dividends.

For investors, in 2014, the challenge will be to ferret out companies which will depend less on share buybacks to prop up the EPS and more on organic growth to do the same and deliver stock returns. To seek out companies which will pay out a higher component of their cash surpluses in the form of dividends rather than squander them on buybacks if such stocks are already richly–valued.

End

Disclaimer

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither its accuracy and completeness, nor the opinions based thereon are guaranteed. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This information is directed at accredited investors and institutional investors only.