The investment management industry is used to trends coming and going; the fundamental precepts that we follow, however, have remained the same, i.e. buying a company which can generate wealth over the long run, at the right price. Many a time market fads pick up one premise and place excessive emphasis on it before moving on to the next trend. Occasionally, however, some of these trends become entrenched and end up getting absorbed into the core principles as the marketplace evolves in response to a changing environment. ESG is one such concept. It has always been lurking in the background in some form or the other but is now making its presence felt at the forefront of the investment decision making process.

For more than half a century the corporate landscape, initially in the Western world and later increasingly around the world (as globalization spread), revolved around the primacy of shareholder wealth maximization. This has sometimes led to extreme outcomes and occasionally scandals. But as economies have evolved, the recognition of corporate responsibility and its impact on society have come to the forefront, resulting in a re-evaluation of the rules of engagement of companies with all stakeholders. We at RVAM believe that we are in the midst of seeing a fundamental shift taking place in the framework of principles around which corporates are organized and based on which they engage with stakeholders. Investors are increasingly recognizing this and are often actively involved in shaping this evolving paradigm.

The clarion call for this was the statement issued last month by a group of top U.S. CEOs outlining a modern standard of corporate responsibility “for the benefit of all stakeholders”.

The Friedman Doctrine

For more than half a century now, the role of the corporation in modern capitalist society has been defined by the doctrine made popular by Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman, enunciated in his famous September 1970 article in The New York Times titled “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits”.

The doctrine recognized the fact that corporate executives as agents of shareholders are bound to maximize profits within the boundaries of the law while social responsibility ends up becoming a tax and an encroachment on functions which are the responsibilities of other arms of society, i.e. the government, civil service, political class or judiciary, which have been tasked with, among other things, the role of deciding on taxation and are given powers to adjudicate and spend these taxes for the benefit of society. The fundamental premise rested on the belief that in a rule-based system, the free market was the best mechanism to allocate resources efficiently, while democratically elected agents formed the laws and the rules of engagement to fulfil the need for social equality and redistribution through taxation; they were accountable to society for fulfilling those obligations.

Changing Landscape

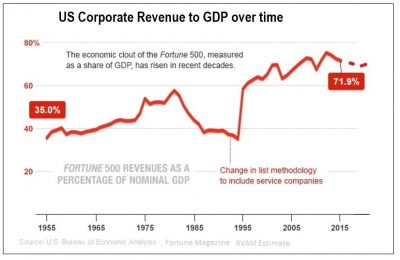

The Friedman doctrine was well accepted and became the de facto model in the second half of the twentieth century, a period when most corporations were largely domestic in nature, operating within the boundaries of their countries and subject to home market rules and regulations. This was also a period of time when the size and economic clout of corporations in the U.S. economy kept growing. The graph below shows how revenues of U.S. corporates (as a percentage of GDP) nearly doubled over this period.

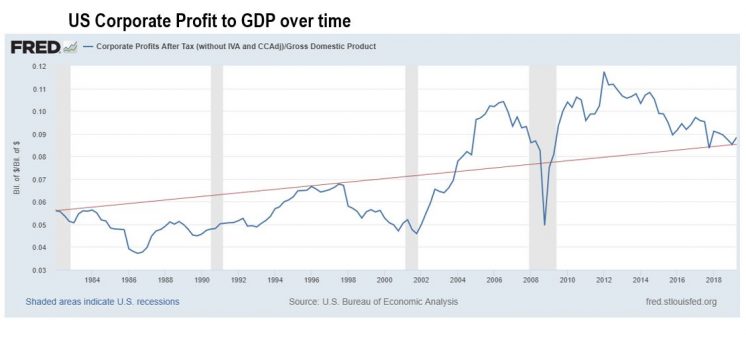

Emerging trends in technology, the ease of moving capital and the WTO all resulted in a new and powerful wave of globalization in the latter part of the twentieth century, which tremendously benefitted large corporations that had organization structures and the means to increase reach beyond their home market success. Corporations not only expanded operations to cater to new markets but also started reorganizing operations and production facilities globally with an aim to increase efficiency and maximize profits (though often at a social cost in their home countries where workers faced the deflationary impact of globalization). We can see the impact of that in the graph below, where U.S. corporate profits as a share of GDP dramatically rose in the twenty first century as they reaped the benefits of globalization.

Impact of Globalization on Taxation

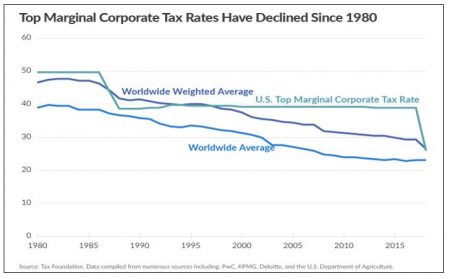

The era of globalization in the twenty first century has not only resulted in corporations becoming a bigger part of society but has also seen a new phenomenon – the competitive race to the bottom on corporate tax. As countries started competing with each other to attract business, governments were forced to offer incentives to fleet-footed global organizations to locate their operations in their jurisdictions. In an era where goods and services could easily move across borders, lower tax rates became an attractive tool to incentivize corporations. The trend, which started in East Asia, has slowly percolated around the world as countries were forced to match incentives to keep jobs and corporations within their countries. The latest large economy to jump onto the bandwagon was the U.S. which, under the administration of Donald Trump, cut its marginal corporate tax rate dramatically starting in 2018. The chart alongside shows the global trend of falling marginal rate of corporate tax over the last few decades as country after country brought down the rate at which it was taxing corporates.

Corporate tax rates which used to be in the 40-50% range in most developed economies of the world have now come down to the 20-30% range, if not lower. In the U.S., corporate tax revenue, which accounted for nearly 6% of GDP at its peak in the 50’s, has shrunk to around 1% of GDP in present times. At the peak of the post World War-II boom in 1950, when corporate pre-tax profit was 13.3% of national income, the after tax profit came in at 6.3%, i.e. more than half the profits made by a domestic company were being surrendered to the government. In the current decade, in the peak year of 2011, when pre-tax profits were 13.6% of national income, the after tax profits stood at 11.4%, i.e. the share of the government in profits had shrunk from over half to only 16.2%. Clearly, with corporates contributing a smaller part of the pie in government revenues, the fundamental premise of the Friedman doctrine is up for challenge.

Implications for the Social Contract

The trend of the rising clout of global corporations that account for an ever larger share of the global economic pie (GDP) along with a higher share of surplus (profits) at the cost of other stakeholders, whether they be workers, governments or society at large, has put tremendous pressure on executives of corporations to act as good corporate citizens and share the social burden which other institutions are struggling to deliver, many times due to a lack of resources. This societal demand is getting translated into calls for investors to hold the companies they invest in accountable, not just for profits but also to be agents of change by incorporating a broad set of ESG principles in their activities and mandates.

Moreover, it is not just investors who are adjusting to this new environment; increasingly large corporate executives and boards are taking a relook at their mission statements to adapt to emerging circumstances. On August 19, 2019, the Business Roundtable (BRT), a non-profit grouping of CEOs of major U.S. corporations announced a new purpose for the corporation; they explicitly stated that “no longer do corporations exist principally to serve shareholders” and also outlined a modern standard of corporate responsibility “for the benefit of all stakeholders.”

Since 1978, BRT has periodically issued “Principles of Corporate Governance”. Each version of this document issued since 1997 had endorsed principles of shareholder primacy attuned to the Friedman doctrine. For the first time, the statement looks at changing the paradigm with a standard for corporate responsibility which places ESG principles on the same level as profit maximization. Change takes time, but as a start, this new debate around purpose is positive and aligns the interests of various stakeholders and propels them to work towards a common goal rather than confront each other across a bunch of clashing ideologies and objectives.

Rising Global Awareness

Sharing the economic pie is not the only reason why ESG issues are becoming more important in contemporary times. While rapid globalization brought prosperity to many billions, it coincided with rising concerns about the environmental impact of growth as well as the real-life issues of dealing with climate change. The World Economic Forum (WEF) each year does a survey of over a thousand global decision makers to understand the risks that they see on the horizon, evaluating them both on likelihood and impact. A decade back (in 2010), four of the top five risks were economic in nature. However the latest report in 2019 has seen a dramatic shift in risk perception, with four of the top five identified risks being environmental in nature and the fifth and most potent one being cybersecurity. The two charts below map out the identified risks on a risk spectrum of Severity and Likelihood across two time periods.

The shifting pattern of dots on the two graphs clearly highlight how decision makers, who a decade back used to worry about economic risks, are now increasingly worried about the impact of environmental and social risks on their business and operating environments. While economic issues have not faded, the perceived risks from environmental issues have dramatically gone up, overshadowing economic issues. Over the decade the two have swapped places between the top and bottom quartiles of the risk perception matrix.

History of ESG in Asset Management

ESG can be considered an information category like many other bits of news or information which goes into the making of an investment mosaic. Its prominence to the value equation has risen due to increasing awareness over the last few years, the reasons for which have been elaborated in previous paragraphs. Of the three pillars of ESG (E – Environment, S – Social, G – Governance), the third – governance – has always been a key part of most investment theses. The environmental and social aspects of ESG are gaining prominence now as, (i) their importance to society is rising; and, more importantly, (ii) the increasingly availability of standardized Environmental and Social indicators in company reporting has made it easier for investors to formally integrate them into their investment process, instead of using ESG as an informal gating factor. A secondary reason for this is the rising awareness among corporates that investors are an equally important stakeholder in ESG disclosures as much as civil society, NGO’s and governmental organizations towards whom most historical disclosures were targeted.

The early years of the investment management industry, stretching back a few decades, was characterized by some mandates which were exclusionary in nature due to the moral, ethical or religious beliefs of the asset owner. These mandates typically excluded companies operating in certain industries (like tobacco, alcohol or arms). The Asian Financial Crisis, followed by the bursting of the technology bubble in the U.S. and the Enron accounting scandal, reinforced the need for extra vigilance on governance issues while investing. The Global Financial Crisis in 2008, which had a widespread impact on society, not just on the financial markets, resulted in calls for considering the societal impact of financial decisions. Asset owners and governments started demanding that investment managers take into account the societal impact of corporate activity as part of their fiduciary duty.

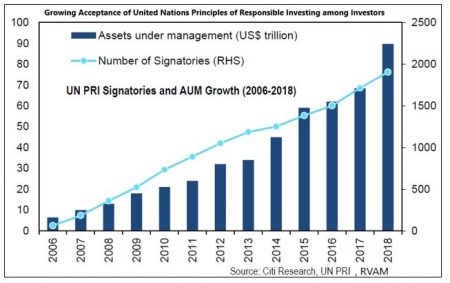

The United Nations in April 2006 launched six Principles for Responsible Investment based on the notion that ESG issues can affect the performance of investment portfolios and should therefore be considered alongside more traditional financial factors if managers are to properly fulfil their fiduciary duty. Consequently, ESG issues are now coming to the forefront in investment processes, though the underlying principles have always been flagged to investors under various guises. A CFA Institute survey of global investors in 2017 showed that 73% of managers took cognizance of ESG issues when making investments. The public commitment to ESG is apparent in data published by the United Nations as, over time, more and more institutions have actively signed up to these principles as shown in the graph alongside.

RVAM’s Approach to ESG

Writing about “Corporate Governance and Asian Challenges” in our September 2017 newsletter, we mentioned that our core objective when investing assets is to protect capital and earn a reasonable return without taking excessive risk. Within that framework, we look at ESG issues as risk factors which need to be identified and evaluated to ensure that the investment objectives of our clients are achieved.

Many asset managers (and indices) use exclusion lists to screen out companies on static ESG factors. This skews the investment universe and the opportunity set based on predetermined factors which are in fact dynamic. Moreover, this does not give credit to potential future changes and the positive or negative impact they could have on the operations of the company or on society. Also, we find that standardized scoring often results in “Green Washing”, where corporates use ESG reports to burnish credentials rather than truly integrate the relevant metrics into their corporate strategy. On ESG issues, we at RVAM focus on the materiality and impact of various factors on the future cash flow generation ability of a company and thus look to integrate ESG into our analysis.

The investment case for every security has two aspects – one, the ability of a company to generate cash flows and use them to grow the business and second, the risk ascribed to the cashflow stream by the market and the consequent risk premium used to discount it. In some industries ESG issues can be a cost of doing business and result in a lowering of the future free cashflow generating ability of a company. In others it may be more about risk management and ensuring that social issues (like health and safety, diversity, labour practices) do not become a reputational issue that are not properly captured when evaluating financial metrics. Ultimately, as investors, we need to be confident that we are getting adequately compensated for the risk taken with the underlying investments. Predictability, a key focus of our investment discussion, requires us to evaluate all future risks and be able to quantify the potential impact.

End

Disclaimer

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither its accuracy and completeness, nor the opinions based thereon are guaranteed. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This information is directed at accredited investors and institutional investors only.