As we move from spring to summer in the Northern Hemisphere, there is a perceptible change in the climate in the key financial markets. A combination of events has contrived to slam the brakes on the rally in commodities across the world. Bond prices are rallying again, the dollar continues its charge higher, stock prices have swooned and are struggling to stage a rally; and commodities have turned sharply lower. All this has happened at a time when inflation prints stay very high and unemployment stays stubbornly low.

In the last quarter, the moves in financial markets have been rather sharp and the shift in the narrative swift. It remains to be seen if this palpable change of heart sustains through the summer. The view that a recession is at our doorsteps has gained currency rapidly almost to the point where there is a resignation to its inevitability now. This is leading investors to view the world in a different light and has in turn led to a behavioural change towards all financial assets.

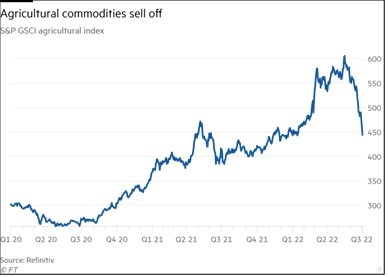

Commodities has been a key asset class that has taken it on the chin in this period, slumping amidst this crescendo of recession expectations. The reasons trotted out for this swoon are rising interest rates, tightening financial conditions, China’s COVID lockdowns, the continuing war in Ukraine, and consequently slowing global growth. There is also a growing view that inflation may be peaking soon with the rolling over of commodity prices across energy, metals and food over the past month.

The supply side for the ingredients that are vital to support global megatrends such as the green energy, green mobility, demographics and technology (IoT, 5G, smart computing, etc.) remains challenged. All these will require much larger amounts of commodities than are being produced currently.

Moreover, the supply-side picture has been ruptured badly this year by a paradigm shift in the global political order following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia is among the world’s largest producers and exporters of key commodities such as wheat, pig iron, natural gas, crude oil, nickel, etc. It also accounts for a significant share of coal and refined crude and aluminium exports. When we combine Russia with its friend Belarus and now foe Ukraine, we can add critical items such as fertilizers, cooking oils like sunflower and rapeseed, chemicals for explosives (ammonium nitrates) among others, which the world finds itself suddenly short of. Shortages for these products is not going away anytime soon, given the protracted nature that this conflict could take and the concomitant uncertainty of their supply in future.

Should the war end sooner, Russia’s now ‘pariah’ status will mean that a certain portion of supply will have been almost permanently lost or impaired for many years, for which there are no readily available alternative sources. In addition to this, we have countries such as China, India and Indonesia asserting their right to self-sufficiency, and thus erecting export barriers for stuff that the rest of the world also needs.

We usually think of hard commodities when we generally talk about commodities. It is important, however, to view soft commodities – mostly agricultural -and hard commodities – mostly metals, minerals and ores – as two distinct sub-classes. The factors that impact and create their cycles are germane to each and the length of their cycles too can vary substantially.

Soft/ Agricultural Commodities

Agricultural commodities like soya bean, corn, wheat, sugar, coffee and cocoa have their own supply-side problems. Being crops, these commodities have shorter supply time frames, linked to their cropping cycles. But within these cropping cycles are long term trends that have perceptibly shifted over many years, even decades, of stagnant to slow production growth. This has been caused by lower availability of arable land (hence limited growth in cultivation), changes in global weather patterns owing to global warming, pressure on and competition for water of water-tables from growing human populations. Add to these the flattening or declining productivity of aging plantations (palm oil, rubber), the rising cost of farm labour and low mechanisation of farms in many developing countries, and one can see the many factors that have contributed to weak supply response.

This has been happening at a time when global demand for food grains, fruits and vegetables and cash crops has been growing inexorably, putting ever more pressure on land and production systems. The adoption of ESG practices, while commendable and much needed, has often worked at counter purposes by eliminating a fair degree of production of these commodities that did not conform to such tenets.

Sceptics may argue that one year’s shortages could be short-lived as a new crop arrives the following year, and that supply will be restored. The problem with this thinking is that production is not growing by much over time and, in many cases, even declining in a normal cropping year, especially for such commodities as palm oil and other vegetable oils, as we wrote about previously https://www.rivervalleyasset.com/the-other-oil-hot-and-in-a-super-cycle/. Barring a year or two of demand-supply being balanced, the system has now become vulnerable to short-term external disruptions and weather anomalies that can disrupt the delicate demand-supply balances within a short period of time. To fix these permanently will require the world to rethink several issues related to food security, climate change and social development, which will take many years of work.

The other problem with soft commodities is that given their heavy reliance on weather and soil conditions, they are geographically concentrated and hence any solution related to their supply must come from the actions taken by the governments of those countries. Also, if one or more countries is impacted by externalities such as Ukraine has been recently, it upsets the delicate demand-supply balance in which the world has been living for many years now.

There are also allied problems such as storage, transportation and processing bottlenecks that lead to wastage and rotting of soft commodities in many countries – problems that have not been fixed yet. There is a silver lining here that if some of these issues are fixed, that could alleviate some of the tightness in the supply-side of the equation.

Hard Commodities

These have similarities with soft commodities in terms of supply-side issues. The current shortages or weak supply response situations that we are seeing today existed pre-pandemic in commodities such as crude oil, copper, aluminium, nickel, lithium, etc. The Ukraine war has exacerbated the situation, putting hard commodities under the spotlight and making the world aware of the real problems that lay buried previously. This awareness of the supply tightness, in turn, combined with the low interest regime and abundant money printing by central banks, led to financial speculation in most commodities, making a bad situation worse, leading to a boom in commodity prices almost across the board over the last two years.

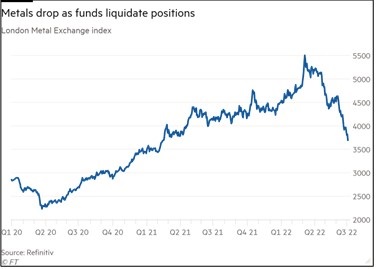

This is now reversing quickly. Hard commodities’ prices have tumbled from historic highs, as investors reverse bullish bets on everything from copper to oil, as recession fears grip financial markets. Such steep declines come as major central banks turn the screws on monetary policy, hiking interest rates in an attempt to curb runaway inflation. Investors are fearful that higher borrowing costs will derail the global economy after rapid price growth has triggered a sticker shock to the cost of living.

Hedge funds have been key sellers contributing to the recent price declines across commodities, selling out of long positions and often replacing them with bearish wagers. Although physical supplies of many raw materials remain tight, hedge funds are taking their chips off the table, thus contributing to the volatility.

A total of 153,660 agricultural futures contracts worth $8.2bn were liquidated in the week to June 28, as per the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission’s latest report. This was the second biggest sell-off of long positions on record, according to Peak Trading Research.

In metals markets, copper was trading down more than 20% this year from the record high of above $10,600 a tonne in April, when it was buoyed by supply disruptions and booming demand as lockdown restrictions eased. Bearish bets on copper currently stand at their highest level since 2015, according to Marex a commodities broker, with hedge funds net short 60,000 lots, or 1.5mn tonnes, of the red metal across all markets at the end of June, up from 4,000 lots at the start of May.

Concerns about the Chinese economy going into free fall are growing despite some improvements in the Chinese macro data, and there seems to be a nearly unanimous view that the U.S. and European economies are heading into a recession. There could be ticking time bombs in the credit markets that could lead to a deeper downturn.

There is also the case of some pre-buying or hoarding of some metals, given the cheap sources of funding available and the supply-chain bottlenecks that constrained their just-in-time availability. Now that financial conditions have tightened and the spectre of recession looms, those who hoarded have been quick to release this physical inventory into the market, pressuring prices further.

All this is about the here and now. But what about the future of hard commodities? The answer to that has not changed much at all. The long-term thesis remains intact, although the time frames may have to be adjusted should we get a protracted and harsh recession.

There remains limited new investment in capacity among energy companies and miners, who remain dogged and disciplined when it comes to investing in new capacities and E&P activities. Instead, almost every large oil major and mining company today continues to promise and pay out large and growing cash returns to shareholders through dividends and share buybacks from the record profits they have generated from previously elevated prices.

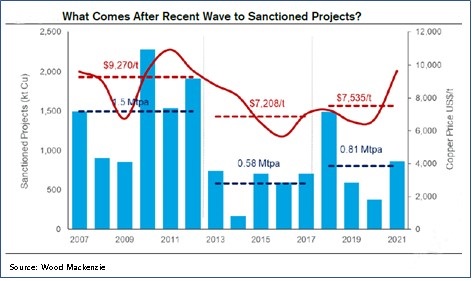

The question to be asked for every such commodity is what is the incentive price required for the industry to change this behaviour and be willing to begin a fresh wave of investments to meet the demand in the future. Industry players are also seized with the realisation that lifting or mining costs have risen substantially today versus historic levels and that they need a much higher price of the commodity to sustain for much longer before they have the confidence to invest so that they earn RoIs their shareholders will be comfortable with. This has not happened thus far and the pandemic only served to delay that process even further.

Take Copper for example (see the chart alongside). According to Wood Mackenzie, 0.81mt of copper capacity sanctions between 2018-21 will have a cash cost of $7,535/t. This is close to where prices are today. Clearly, when this capacity comes on stream, it will generate low returns for companies. On a production base of nearly 24-25mn tonnes, although this is barely 3% of current capacity, it highlights the high cost of bringing new capacity on stream.

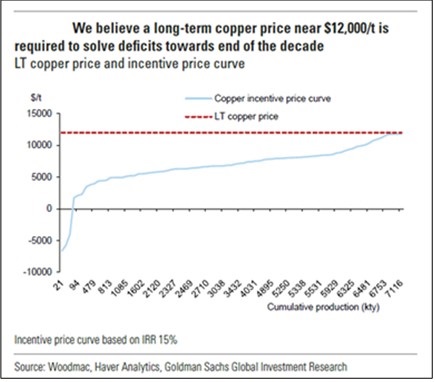

To answer the question of the incentive price of copper, the team at Goldman Sachs believes it is near $12,000/ton or ~ $5.4/lb. Copper prices have traded close to $5/lb earlier this year, but not for long enough and prices are still below the incentive level needed for large miners to consider announcing new projects. Given climate change concerns and an ESG-conscious policy framework which seems likely to persist, these companies are themselves caught in a bind.

Another problem to be thinking about is that even if the companies were willing to invest in new greenfield mines or even expand brownfield ones, the sanctioning process is hugely time consuming in the countries where such reserves reside, such as Chile, Peru, Zambia and Australia. Sanctions are known to take a minimum of two to three years, sometimes longer, before mine development can begin.

To turn to the demand side of things, the driver that is likely to make its presence felt in a much stronger fashion soon is acceleration in the adoption of Battery-Electric Vehicles (BEVs). As their adoption accelerates further, there will be a need for ever more nickel and lithium for batteries and for copper and aluminium in the cars.

While we do not wish to belabour the point, these BEVs will consume significantly more copper in wire-harnesses and electrical components and aluminium in body parts and interiors; even precious metals like palladium and rhodium will see a new source of demand in future. In addition, renewable sources of energy such as wind-turbines and solar panels and the incremental construction of power grids and transmission infrastructure, are all large potential sources of demand for commodities.

Crude oil has a similar story, although there are strong views to counter the bullish demand case. It is accepted by even the bears that the supply side of the story is on a weak wicket in the long term and, barring a large substitution of crude oil and its derivatives and refined products and a price-driven demand destruction, the world will remain hooked to it for a long time to come. The geopolitics of crude oil add a dimension to its price which is always in the realm of conjecture for most of us. Yet, even those events do not point to a situation where the market is copiously supplied in future, given the sheer paucity of new large crude exploration projects in the past several years that could replace existing ageing oilfields which have either plateaued production or have already gone into a decline.

Top, Bottom Or Correction?

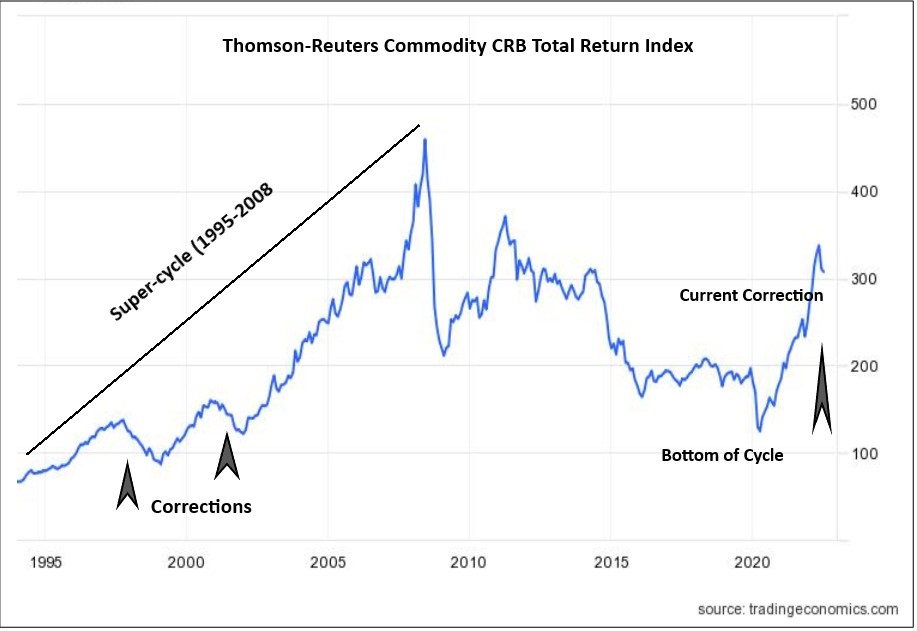

The view for the next few quarters and months is full of uncertainties. However, if one were to hazard an educated long-term view of the commodity cycle (beyond the next two years), it appears that the present correction could well be a pause in what is a multi-year bull market whose origins insofar as prices are concerned, could be traced back to the 2020 lows at the height of the pandemic.

Take a look at the accompanying chart of the Thomson-Reuters CRB Commodity Index since 1996. It shows that the last big commodity super-cycle lasted nearly thirteen years from 1996 until the GFC in 2008-09. What followed since has been a gut-wrenching correction/ decline for the following thirteen years, which most likely ended at the pandemic trough of 2020. If we are reading this cycle correctly, then we have commenced the ascent into another multi-year commodity bull market, whose first leg is perhaps completed. A correction like the ones that occurred in 1997-99 and 2000-2002 is probably now underway.

What will lead to this correction ending, when it will end and how much lower prices have to fall, are all questions whose answers can be merely speculative right now. We will have to traverse this period and be alert to events and data points as they play out before we get more confidence to be calling a bottom.

Looking beyond the realms of demand and supply, some observations of the softer behavioural issues that impact investor actions in the markets would be in order here. They make it plainly visible that we are far away from a commodity cycle peak when viewed on a multi-year basis.

- None of the acts of euphoria that characterise sectors topping post multi-year rallies are present in 2022.

- The share of commodity stocks as a share of indices and as a share of daily traded volumes are inconsistent with a sector which is highly popular.

- Stock-level valuations of commodity companies are far from pervious cycle peaks.

- Management actions, such as large M&A deals and large capex plans, that accompany booming industries are absent.

- Retail investors have not been buying into commodities through ETFs of Commodity Funds at the magnitude that has made headlines such as tech funds have in the recent past.

- Analyst estimates that are linearly bullish for the next three to five years for commodity and mining stocks have been sorely missing and sporadic if any.

Comparing all these characteristics to those of the technology sector which has just come off a euphoric bull market, we find that the technology boom ticked all the boxes above while one would not be able to tick a single box just yet when it comes to commodities. This is a big disconnect.

The New Winners For Now

This will create a bunch of winners and others who will suffer now as the correction unfolds amongst the producers and consumers of commodities. It will also throw up certain countries that will give up some of the gains they made in the last two years from the commodity rally. On the other hand, countries which depend on imported commodities, chiefly crude oil and others, could probably be thinking they just got handed a ‘get out of jail free’ card and heave a sigh of relief!

Among sectors, the consumer staples and discretionary sectors like airlines, packaging materials, tyres, automobiles and components and energy intensive ones like cement are all beneficiaries. These sectors also happened to be the most negatively impacted ones as raw material cost pressures hurt them hard.

On the other hand, countries such as Indonesia and Australia which are naturally resource- and agriculturally-endowed could suffer for a period of time until this correction plays out. At the same time, countries like India and China which are net consumers of commodities, would probably end up having dodged the proverbial bullet, and could now enjoy a more benign monetary and fiscal stance.

What To Look Out For From Here On

There are several tell-tale signs to follow before we have a durable bottom in commodity prices and commodity stocks.

- Analyst estimates of commodity prices in their models currently seem much too high. Most street estimates of demand and supply will need to be pared. Paring these down will lead to sizeable cuts to earnings of miners and commodity driven companies. This paring does not happen in one go usually but over a few quarters.

- We also look out for industry data points – of supply-side actions from producers of commodities like plant shutdowns, outages, sowing-cropping reductions for agri-commodities, weather-led disruptions potentially, all of which could help balance the markets faster and less painfully than many might think today.

- On the demand side, it would be important to track development of the new demand drivers such as growth in EV production, renewables adoption and to sight the inflection in demand that most observers have called out so far. For example, from several accounts the year 2023 is expected to see a big inflection in EV production.

The commodity rally of 2020-2021 has most likely ended. We believe this could be a correction in a larger degree commodity bull market. It can be a deep and vicious one, as we have seen in history. However, given the structural underpinnings of this commodity bull market which, to reiterate, stem from years of under-investment and weak supply responses, it would just be a matter of time before these structural supply weaknesses reassert themselves and the next rally unfolds.

It is impossible to draw up a time schedule for when this might transpire. What is more important is to believe that a long-term bull market in commodities is well and truly underway. For now, it is time to hunker down, take action to protect against further price hits and reposition to gain advantage from those companies and sectors which stand to gain as long as this correction plays out.

End

Disclaimer

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither its accuracy and completeness, nor the opinions based thereon are guaranteed. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This information is directed at accredited investors and institutional investors only.