In a low growth world, growth will be found where structural reforms gain traction.

Watch EM for structural reform.

As world growth takes a downward twist, our hunt for current and future growth continues. Though our base case remains that long term growth rates are clearly down for the foreseeable future, pockets of growth can re-emerge. The exciting point is that these pockets of growth could emerge where ex-growth valuations are most apparent.

We are closely watching a political push towards structural changes in EMs. China is the centre of this push, as being unveiled at the currently on going Third Plenum in Beijing. Markets like India, Indonesia, etc. have similar stories to follow. If the Chinese political system is able to push this through, the wealth creation for the world will be high. We hope to be there, capturing this bonanza.

Emerging Market (EM) growth at crossroads – “structural reform or not”

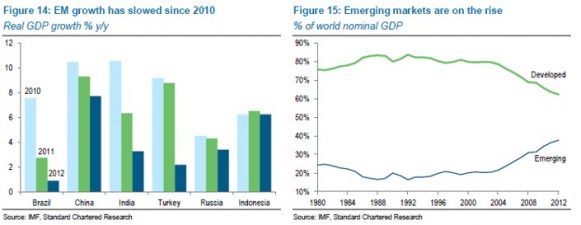

Large chunks of the emerging market space have hit a growth air pocket. Though they continue to outpace developed market growth, their growth has slowed down vis-à-vis their own history (see charts below).

The actions required to get out of these “air pockets” and realign with their upward growth trajectory are primarily related to structural change. The lynch pin of this argument is China. It has hit a per capita GDP range associated with the “mid-income” country malaise. This, in other words, is the condition when economic growth tends to slow down dramatically when per capita GDP hits the USD 10,000 p.a. “mid income” range. This is because the next stage of growth normally requires a large dose of structural reform. This often includes a strong dose of Schumpeter’s “creative destruction”. For most EMs this creative destruction is difficult to execute – the two exceptions to this are Korea and Taiwan. If China manages that leap as well, the opportunity to create wealth will be enormous – both in China and in businesses across the world.

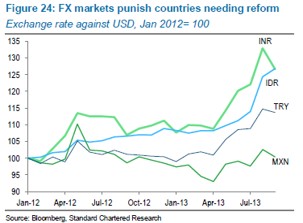

A similar argument, though to a smaller degree, can be made in countries like India, Thailand, Turkey and Brazil. Some of these countries are not at the mid-income level yet but they are in need of a new dose of structural reforms. Hence we would like to take a slightly closer look at this phenomenon. Where this reform has stalled the markets have punished the countries – either by a strong de-rating of the equity market (e.g. China, Russia) or a crash in the FX markets (e.g. India, Indonesia) as illustrated in the charts below.

China (and India) is expected to grow much slower

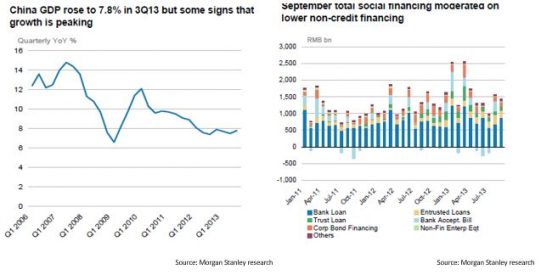

China’s growth has dramatically slowed down over the past six years. Also, it is clearly headed towards a lower growth future. More importantly, the quality of growth has been decreasing with increasing credit intensity to achieve the same level of growth. Though there seems to be a temporary, credit-led bottoming of this growth, the trajectory could go lower in the absence of the required structural change (see the chart below on the left). The chart on the right shows the sharp increase in total social financing (China’s surrogate for liquidity) in the last two months.

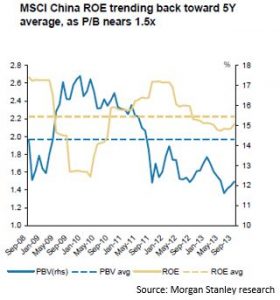

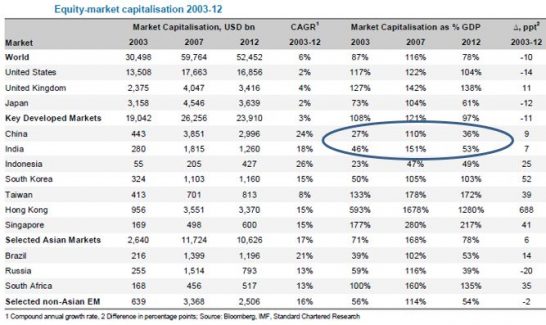

The expectation of future Chinese growth has also been pared down dramatically over the past six years. Stock market earnings are priced for negligible earnings growth into the future. China’s and India’s market capitalisations as % of GDP are back to where they were in 2003 and less than half the peak of 2007 (see table below). We think this ratio has bottomed and markets will now grow in line with nominal GDP growth.

This low valuation has created a situation where structural initiatives that stabilise growth and improve its quality would lead to strong wealth creation. The new Chinese leadership seems to be pushing its initiatives on this front.

China’s structural initiatives

The new Chinese leadership has been trying to build consensus towards larger structural reforms. Like in any political system there are strong vested interests opposing it. These vested interests include local (village, city and provincial level) governments, large SOEs (State Owned Enterprises), ruling elite, corporate powers, etc. The leadership’s ability to fight this will determine the success of its structural initiatives more than the details of the initiatives themselves. The multitude of corruptions cases against the largest SOEs in the past few months is also a manifestation of the struggle against these vested interests. Also the opening up of the Shanghai Free Trade Zone is the pilot case for the path towards a lot more open China.

The potential reforms would be under the following topics:

1. Financial Sector liberalisation

This will primarily include:

- Interest rates liberalisation. This will have the biggest impact on deposit rates and help the saver over the borrower i.e. individuals over corporates.

- An improved and a deeper bond market – both government and corporate bonds. This could be one of the solutions to the local government debt problem as it moves from “corporate loans” to “government bonds

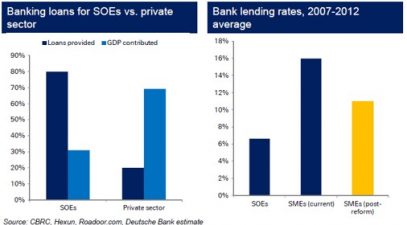

- Better access to credit for the private sector. This is an important reform as it will unshackle the local private sector and create a more level playing field with the SOEs. The chart on the left shows that the private sector in China contributes to 70% of the GDP but avails only 20% of total loans. Also, the cost of credit for SMEs, which is the surrogate for the private sector, is more than double that for SOEs, as shown in the chart on the right.

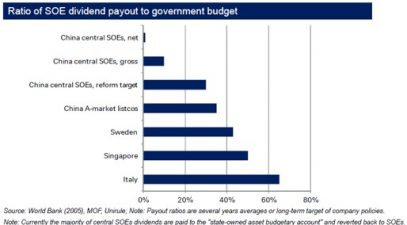

2. SOE reforms: This primarily entails improving the efficiency of SOEs and increasing shareholder returns from SOEs (the largest shareholder being the government itself)

This is a very important point as it follows our thesis that Chinese companies are going to generate more cash and will pay out more cash too. The chart on the right shows the government’s targeted increase in dividend contribution from SOEs.

3. Further opening up to foreign and private investments (especially in the services sector)

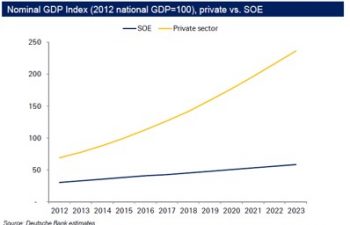

This is where risks and opportunities are the maximum. Consequent to this, the private sector’s share of GDP will rise dramatically – moving from 70% of current GDP to about 240% of current GDP by 2023 (see chart on the left). The other important thing to remember vis-à-vis this point is that the private sector also includes a large chunk of contribution from subsidiaries of global MNCs. Thus buying these MNCs would be another way for us to participate in this wealth creation.

End

Disclaimer

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither its accuracy and completeness, nor the opinions based thereon are guaranteed. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This information is directed at accredited investors and institutional investors only.