Every few weeks the US Federal Reserve Governors get ready to meet and take stock of the US economy. Around that time the world at large and those in the financial markets in particular begin wringing their hands, break into a sweat and the narrative turns shrill. Will she, won’t she? Now or later? June, September, December? This year or next? The decibel levels reach a crescendo and then the tumult dies only to resurface on the eve of the next meeting. This has been repeated ad nauseum for several months now.

The US Fed Governors, Janet Yellen and her predecessor Mr. Bernanke, have on their part been equivocal, prevaricating and taciturn. With each passing Fed meeting the forward guidance changes, the tryst with the ‘normalisation’ of interest rates is pushed further back. The basis for the decision is stealthily modified.

A year ago Wall Street and the world had pretty much etched in 3%+ 10-year Treasury yields a year out, some talking of getting used to seeing a 4% handle soon enough. That interest rates are now below 2% is a source of consternation for them.

We at RVAM have held a non-consensus belief through much of this raging debate and the tightening tantrums. Meanwhile, we have also been reading about the travails of the Swedish Central Bank, the Riksbank over the past few years. The lessons of their misadventure are surely not lost on any Central Bank in the world.

The Riksbank prematurely tightened interest rates (it now appears so on hindsight) and then had to roll them back equally quickly as the deflation monster came knocking on its doors. In fact, we may say that this experience of Riksbank haunts the US Fed.

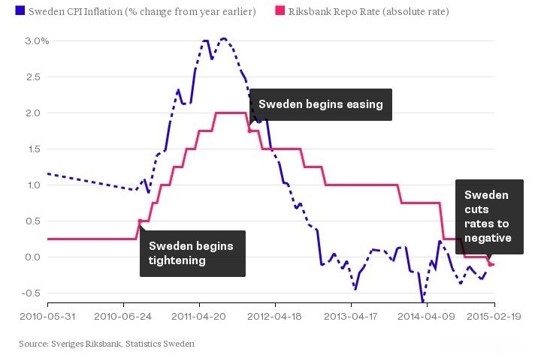

To recap, in 2010 in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crises, Sweden’s economy was among the first to recover and inflation began to rear its ugly head in the land of the Vikings. The Riksbank, to stave off the threat of an over-heating economy, began tightening interest rates from the middle of 2010 and took them all the way from 0.25% to 2% within a one year period, almost exactly in step with rising CPI which rose from 1% to 3% in that period.

Before long deflationary pressures arrived uninvited, mostly from the Euro region (its biggest trade partner along with its two Nordic neighbours) and began to have a telling effect in 2011. Inflation reversed quickly heading sharply south. By the beginning of 2012, the Riksbank was back in easing mode, desperate to stave off deflationary pressures. Alas, to no avail. Deflation overtook its best efforts by late 2014 and Sweden became another high-profile prey to the deflation monster.

The Riksbank’s critics came out in full force, even as the world’s Central Banks raised their eyebrows and took note of the dramatic turn of events all in a matter of eighteen months or so. Only recently Sweden has undertaken its own small QE worth a piffling $1.2bn and promised to do more if required.

Janet Yellen and her cohorts are well aware of these events. They want to raise interest rates this year if conditions are right. They also want to be sure that their actions do not trigger off a disorderly adjustment to the new paradigm. What also haunts them is that while the unemployment rate has been brought down, the economy has fallen well short of the 2% inflation target for the past thirty three months, and looks far from getting there anytime soon.

The irony is that QE in Japan and now in Europe has indirectly contributed to the strengthening of the US Dollar, something the Fed would not have hoped for. The outcome is that this is having a further deflationary drag on the economy along with the sharp decline in crude oil prices. How rapid this decline in inflation will be is something we will only know in the months ahead.

We do not think this is lost on the Fed either. They have witnessed first-hand the outcome of the Swedish Central Bank’s actions and the hit they took to their credibility in its aftermath. The US economy’s global importance being quite a bit higher than that of Sweden, the Fed will have to be extra careful that the pressures from the markets do not overwhelm it and forces its hand all too soon.

The past experience of Fed rate normalisation has shown that once it begins to move in a certain direction it tends to continue on that path steadfastly. Will the Fed make this first upward move in rates and then decide to fly at that low altitude for a long period of time as the expected economic recovery remains elusive? Or will they then continue to take the Fed rate further higher towards its normalization target regardless? What purpose would a single 25 bps rate hike in 2015 achieve towards its goal of achieving 2% inflation and a stable GDP growth? What is the point of ‘lifting-off’ anytime soon only to realise that flying any higher carries the risk of burning out!

Our take is that two things could transpire in the months ahead. The Fed has said it will be data dependant only recently, while shifting away from its much debated ‘patient’ stance. If so, the deleterious effects of the strong greenback and its drag on inflation and GDP growth will show up in the data before long. In the face of that evidence, the Fed will find it virtually impossible to make a strong enough case to move towards normalisation of interest rates. The interest rate hike chatter we witness every other month could then be quietened on Wall Street for 2015 with the markets left wondering if this is now a 2016 event, if at all.

Having pushed the date out to an unknown period ahead, it could then begin to focus on the dreaded ‘D’ word – Deflation. That deflation has perhaps waded across the Atlantic from Europe and from Japan over the Pacific, could become a harsh reality. How will investors react to this change in paradigm when confronted with such a scenario? Is it even conceivable that if the US were staring at a deflationary threat twelve months from now, the notion of QE4 would be floated? This may not seem as preposterous as it appears to be today.

Much of what we mention here could yet be conjecture. But equally, it is not entirely improbable or impossible. The probabilities of such events will rise or decline through summer as data arrives and drives these debates. We are prepared to rule out nothing. For the Fed, all options are on the table. It is certain though that volatility on the back of these will not die down and could perhaps even rise.

End

Disclaimer

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither its accuracy and completeness, nor the opinions based thereon are guaranteed. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This information is directed at accredited investors and institutional investors only.