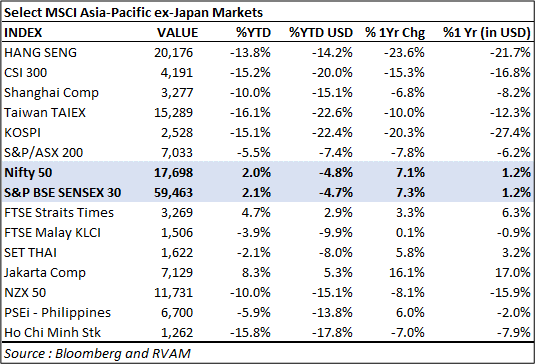

Few markets in Asia have shown the resilience that India has, over the past one year. While the headline Benchmark Nifty 50 index has not been on a tear, it is nevertheless up on an YTD and 1-year basis by 2% and 7.1% in local currency terms respectively. This despite the fact that India has seen foreign investors turning heavy sellers during this period (for the first time in many years). Valuations – cut any which way – make it one of the most expensive markets in absolute terms, relative to its own history, relative to Asia ex-Japan or Emerging Market indices and its peer countries. The weight of outperformance and valuations rests heavily on the market where it stands today. The burden to deliver on the lofty expectations embedded in those figures lies immediately ahead.

Oddly, this comes at a time when global economic stress is rising and recessions are at the doorsteps of the US and Europe. The world is beset with several serious issues such as record high levels of inflation globally (and even in India where the CPI is at around 7%), the supply-related problems unleashed by the war in Ukraine, geopolitical tensions and, finally, China exporting its own Covid-related problems to the rest of the world during this period. India has stood out like a Teflon-coated market for investors to sit out this year.

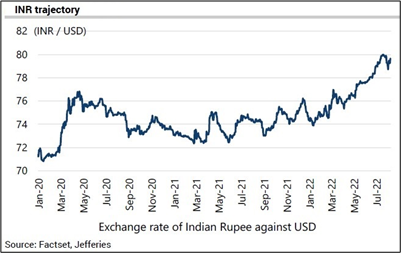

All this has happened for good reasons – India’s corporate earnings were climbing through 2021 and at the turn of 2022 as it came out of the pandemic all guns blazing. So even though crude and commodity prices ran amok, its commodity components in the indices benefitted hugely, driving the index performance to a substantial degree. Further, the weakening of the rupee was also taken in stride as exporters too benefitted from this.

However, now that the commodity tide, as also crude oil prices, have turned sharply lower, those earnings are being cut back in spades. Post the pandemic reopening surge, several companies are beginning to feel the lagged effects of high-cost raw materials, inventory gains of the past are turning into losses and opex costs which were held back for over a year have now begun to normalise. When seen on a two-year stack over 2019-20, the earnings look good, yet a large number of companies are falling short of the euphoric estimates investors had begun to build to justify high stock prices. Quite naturally, disappointments in reported earnings are beginning to hit during this quarter’s reporting season with regularity. This is now being captured by the earnings downgrades to the benchmark index estimates as we come to the end of the reporting season soon.

The macro backdrop in the earlier part of the year has also been benign. The strains are beginning to show from high crude and commodity prices and weakening domestic and export growth as the easy comps of the Covid period begin to wane. Inflation has been sticky in India above the comfort zone of 4% even before it became a global hoodoo this year. The government has managed the situation well thus far, by doing the heavy lifting to shield the masses from the direct fury of imported inflation by deftly adjusting taxes on petroleum products, tweaking GST rates and importing vast quantities of crude from Russia at a deep discount.

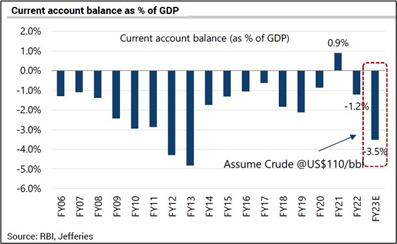

India will be running up a large central fiscal deficit of c.6.5% and a widening current account (targeted to reach between 3 and 4% of GDP from < 2%) this fiscal. The trade balance has worsened, forex reserves are down (but not alarmingly so yet) and the currency has predictably been the fall-guy, finally yielding to pressure against the greenback’s hot streak.

The Domestic Faucet – A Gusher Yet

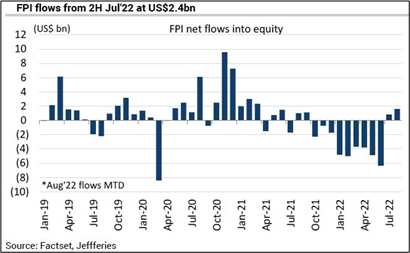

The bull arguments surrounding India’s relative strength are well understood by domestic and foreign investors. While the latter have been selling stocks in India consistently over the past year, the domestic institutional investors have been a solid bulwark to this selling. Current FII selling of US$35bn, amounting to 1% of market cap, is the largest peak-to-trough selling on record, higher than during the Global Financial Crisis. The outflow has been offset by stronger DII (domestic institutional investors) buying US$39bn during this period.

The support has come from the steady financialization of savings of the middle-classes in India over the last few years and which has accelerated in recent years. Such flows into mainly equity mutual fund and direct cash equities have provided the ballast to the market and kept it from sinking under the weight of foreign selling, something we have not seen in similar previous episodes of foreign investor selling.

This stable supply of capital has stemmed from low bank deposit rates, low Government administered savings rates providing little incentive for domestic savings to remain in these low yielding investment products. Further, the confidence in the long-term structural growth of the Indian economy, its sound management thus far and the confidence in the stability of the present political establishment have buttressed investors’ positive view of Indian equities.

Soft issues such as these, supported by liquidity usually tend to have a finite life and eventually succumb to the weight of valuation disconnects and the consequences of economic imbalances in the economy as and when they surface. We sense that this is transpiring, and evidence is beginning to mount.

Flow Is Slowing

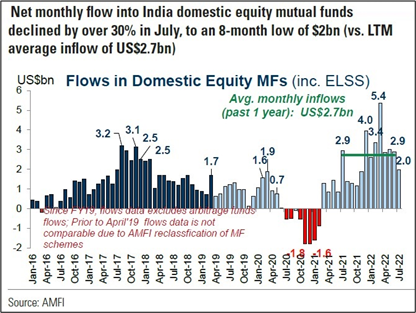

The flow from this spigot is palpably slowing if not turning off abruptly. As per data recently released, flows into domestic equity mutual funds declined to an 8-month low of US$2bn in July, falling by over 30% m-o-m, despite the strong performance of the market in July. Redemptions increased for the first time in the last four months (up 16% m-o-m) to US$1.9bn. In India, Systematic Investment Plans or SIPs have been the big success story driving much of the flows into equity funds. While these SIP flows statistics remain healthy, the average monthly SIP contribution per account fell further in July to Rs. 2160, the lowest level in over a year, suggesting that retail investor appetite appears to be flagging in the face of tepid returns for several equity funds in the past one year.

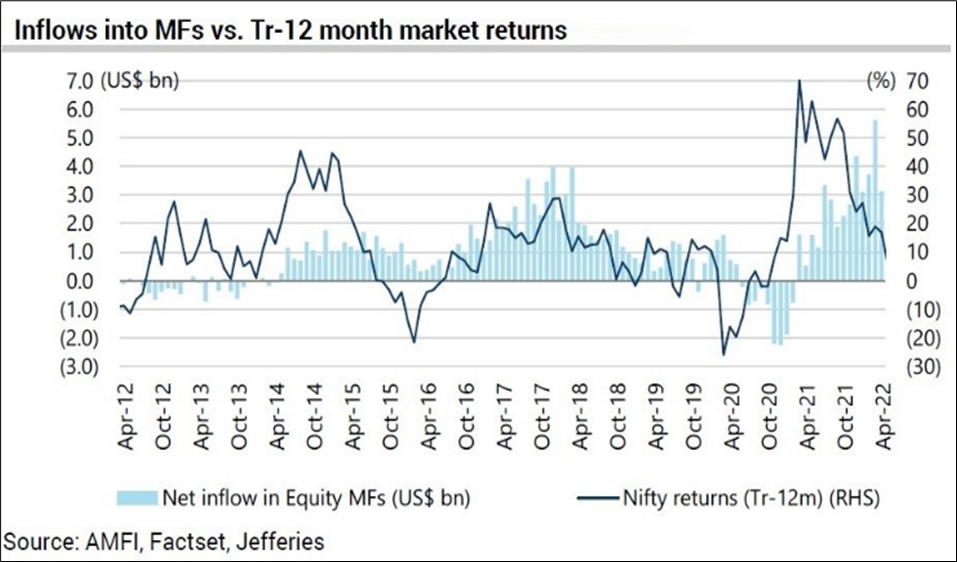

Periods such as late 2015, early 2016, a large part of CY19 saw low inflows as trailing 12-month returns came down to low single digits or even became negative. Hence, there is reason to believe that retail investors are canny allocators and can easily pull their horns in if their targeted returns fall short of their expectations.

Do Not Lose Sight Of The 10-Year Government Bond Yield

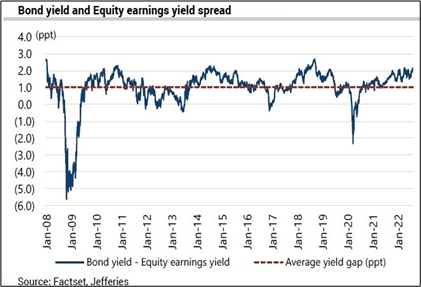

Another factor worth noting is that India’s 10-year government bond yields have risen steadily and are currently near 3-year highs. As the equity/bond yield gap approaches previous lows, it suggests improving attractiveness of bonds relative to equities.

India’s 10-year G-sec rate has pulled back from the recent peak of 7.62% in Jun’22 down to 7.30%. However, the rally in July-August has driven the market’s 12-month forward PE higher to nearly 23x. As a result, the bond yield – earnings yield gap has jumped up further to 2.76%, which is 176 bps higher than the long-term average of c.100bps. Clearly, this is an unsustainable level if you look at the chart alongside. It is an area from where equity returns have turned sharply negative. This gap has to mean revert and readjust before any rally of a larger degree may commence. This remains a serious tail-risk to equity returns in the months ahead.

Deposit Rates v/s Equity Flows – A Close Call

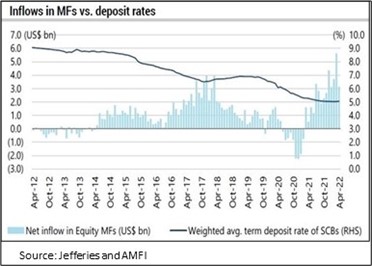

Lower interest rates for bank deposits somewhat correspond with higher flows, but not significantly, with the 2014-15 and 2019 periods seeing high rates but significant flows. The secular decline in deposit rates in India has proved to be a long-term tailwind and enabler of savings being channelled into equities. Were this to reverse in the months ahead, it would surely test the resolve of domestic retail investors in the face of a flat to weak equity market.

The Valuation Case – Sweating Under The Collar!

India’s valuation premium is increasingly making it look like an outlier. India’s sell-side estimates are notoriously pegged perennially a few notches too high and are known to be cut as we traverse through a fiscal period. This year is no different. More than half-way into the earnings reporting season, the estimates have already been cut by 9%. Just empirically looking at sectoral estimates, it appears that in certain sectors there is excessive optimism embedded that needs to be rationalised. Hence, it would not surprise us at all if earning downgrades continue into the latter part of the year.

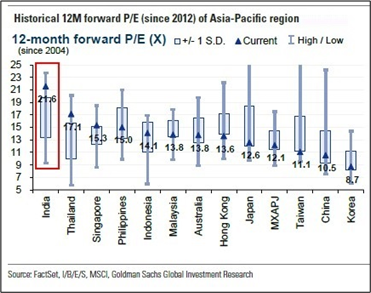

India has rallied by nearly 15% off the recent bottom in mid-June. Juxtapose this rally with earnings estimates declining for the MSCI India Index and we get an expensive market which has just gotten even more so recently, towards ~ 21x FY23E, i.e., +1.6SD of its trading history since 2004!

Why Foreigners Are Possibly Baulking At Buying Any More India

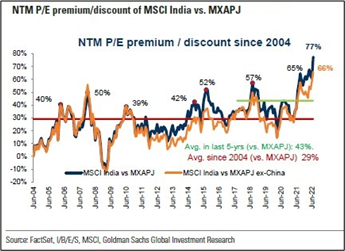

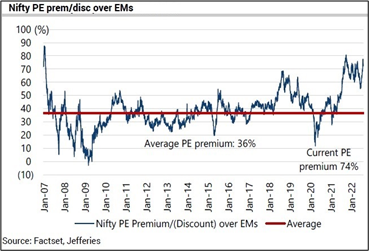

Any foreign portfolio manager or allocator, however bullish on the long-term India growth story, when shown the two accompanying charts, would find it very difficult to push the envelope and allocate any more towards Indian equities than he already might have. In fact, it is highly likely that these charts would persuade India bulls to tactically trim Indian equities in the face of such overwhelming over-valuation, if they have not so far, and those who have sold to perhaps sell more.

India’s valuation premia against GEM and Asia ex-Japan measured over long time periods as these charts portray, tells the tale of a market that is a stark outlier and from where the forward returns over the next six to twelve months are likely to be poor.

Finally, look at how India stacks up against its peers in Asia on valuation grounds. It is the same picture, where it is the only market other than Thailand that is trading well beyond +1SD of its long-term trading history. Ominously, three of its top competing large markets for fund flows – China, Korea, and Taiwan – find themselves on the other end of the scale, being the three cheapest in Asia.

Earnings Downgrade Cycle – In The Thick Of It

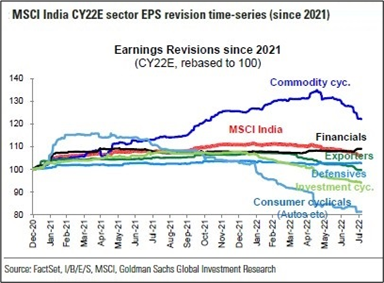

India’s earnings are surprising on the downside rather than turning higher, which is what is required for these lofty valuations to hold and justify the optimism being reposed in the market. Look at the chart below for confirmation. Every sector of the MSCI India Index has seen earnings estimates rolling-over since January, except commodity cyclicals which have finally begun to give way rapidly since April.

India’s earnings upgrades peaked early in the year and have now been cut successively through the summer months and more are happening as the June quarter results roll in. MSCI India’s EPS for FY23E have been cut by 8.9% since they peaked on 29 April 2022. That is not an insignificant number, just getting past the first quarter of the fiscal year. If management commentary is to be believed, the second quarter for key sectors like IT, commodities, energy and pharmaceuticals are unlikely to see any big reversal from the soft trends we have seen thus far. We reckon that the downgrade cycle is unlikely to reverse any time soon, given the current trend of domestic growth and weakening export growth in the face of recessionary conditions globally.

Wrongly Positioned In The Global Context

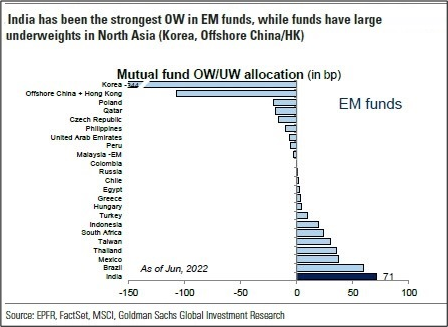

India’s strong stock market performance means that it is now at a juncture where it looks wrongly positioned in plain sight. Once again, India has the large overweight position versus markets like China and Korea among the top EMs and even larger than Brazil, which is the second most over-weighted market.

As per Goldman Sachs research, AxJ and EM focused mutual funds are overweight India by 270bps and 70bps respectively. This is stark, given that foreigners have been consistent sellers in India for the past several months now. It also suggests that foreign investors are simply too stretched in India and may just need a reason to further lighten up.

The risks to India’s market performance in the medium term remain elevated in a global and regional context of valuations being expensive. Global investors are unanimous in their love for the market through the starkly overweight positions held on their portfolios. India’s own macro development is not a pretty picture exactly with the current account and the fiscal balance fraying and the currency coming under pressure. Inflation is declining gently as the benefits of lower crude oil and commodity prices begin to have a beneficial effect for now. However, the risk remains that were crude oil prices to rise again (as they easily can, given the tight-demand-supply equations there), India’s weak underbelly will be exposed yet again. This time, the government may not be in a position to take the burden in its stride again, having done so once before at considerable cost to the exchequer, running the size of deficit it already is.

Today investors’ focus remains affixed on the long-term structural strengths of India. We concur that there are few growth markets to match India’s long-term potential in Asia and EMs. However, investors seem to be losing sight of the risks that the market is exposed to, tail risks that are currently hidden from view and which can easily spring a surprise from any of the global risk factors that today are far from settled. India, therefore, provides a low margin of safety at this juncture from a medium-term tactical standpoint.

Having said all this, we are cognizant that expensive markets, like stocks, can often remain expensive for much longer than one expects. It might well be the case with India too this time, as it has been on previous occasions. It is difficult to answer conclusively what might be the straw that will proverbially break the camel’s back. As we have said earlier, tail risks exist domestically and globally that could easily exacerbate the current status quo and thinking on interest rates and inflation. We believe that the fight on inflation has only begun and is far from over. Just the mere decline of inflation from here should not be equated to a job well done. The US Fed and also the RBI’s mandate to bring inflation to heel should not be forgotten and therefore their actions are more likely to surprise markets negatively in future, given how entrenched inflation seems to be. Beyond inflation, a recession in the Western world can influence growth rates in the rest of the world surely, impacting India’s growth rates too. India’s market reflects huge optimism that it will remain unaffected, will attract capital regardless of price and that it will do so interminably. Such complacency among domestic investors remains high at a time when the global situation on interest rates, inflation and central bank actions are fluid and call for greater caution.

In conclusion, India’s equity market is riding on a tide of high optimism and a smugness that little can go wrong for India from here. It remains at risk of being blindsided by unexpected events for which there is little or no margin of safety in large parts of the market. Investors ought to brace for a period of low to negative returns before valuations normalise and mean revert to a semblance of equanimity. Until then, the market may remain elevated until it eventually breaks down under its own weight of heavy expectations and unbridled optimism.

End

Disclaimer

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither its accuracy and completeness, nor the opinions based thereon are guaranteed. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This information is directed at accredited investors and institutional investors only.