In a period where the financial press is inundated by coverage of rising global uncertainty, whether due to a recalcitrant northern regime playing with forbidden toys or the rapidly falling hopes of an investment-led US boom or the catch-22 bind European policy makers find themselves while setting monetary policy, we thought we would focus on a more mundane but pertinent issue for day-to-day investments: corporate governance in Asia.

Recent events in various Asian markets have brought to focus the differing levels of governance and the implications for investor returns. Last month we saw a de-facto board-level coup in one of the most respected Indian companies – a flagbearer of corporate governance with one of the highest ranks in the region: Infosys. Then we heard that the Vice-Chairman and heir apparent to one of the largest and most successful companies in Asia, Samsung Electronics, was indicted and sentenced to five years in prison. In Hong Kong the news headlines were about how the Chinese communist party had successfully enshrined itself in the articles of association of more than thirty Chinese State-Owned Enterprises listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange.

Investors have, many a time, asked us how we deal with corporate governance issues. Our usual response is that Asia has a diverse set of companies with varying issues so there is no one-size-fits-all answer. The investment team at RVAM, with over seventy years of combined experience, has experienced multiple market cycles and observed corporate governance in Asia evolving over time to fit the changing ecosystem. Ultimately, as investors, we look at all issues through the classic lens of expected return versus the risk being taken to achieve that return. Corporate governance concerns either lower the cashflow return potential to investors and/ or often increase the risk attributable to achievement of that return potential, which in turn may make a great business look poor from an investment attractiveness perspective.

Corporate Governance and Its Impact on Returns

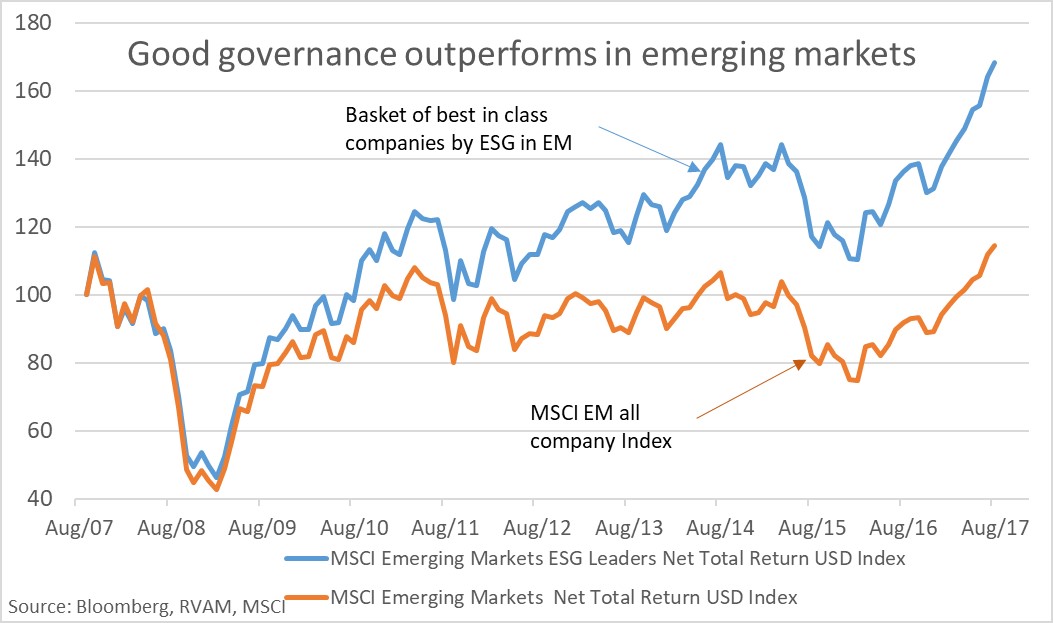

There are innumerable financial research papers which show how returns in the long run are improved by selecting companies which focus on good governance and adopt best ESG (Environmental, Social & Governance) practices. It is not just in developed markets that ESG focus delivers better returns, but also in Emerging Markets (EM) as highlighted by the chart below, which compares the EM ESG Leaders index with the standard EM index.

While Asian indices have limited history, our analysis shows that, over the last decade, a similar collection of ESG leaders within MSCI Asia Pacific ex Japan has delivered an annualized outperformance of 100-150bp (1-1.5%pa) over the standard index.

As investors, we deal with a range of governance issues from relatively minor corporate transgressions to significant concerns about the reliability of financial statements and, at the extreme, outright fraud. While there are some universal minimum governance standards, there is no single yardstick which an investor can use to evaluate all ESG issues of a potential investment as a lot of them would be contextual. For instance, the standards of how one evaluates and holds a mining company accountable for ESG would be very different from those applied to a consumer company.

We look at varied third-party research sources which rank corporates on governance factors. While they provide useful benchmarks, one of the challenges these ratings and surveys face is standardized scoring on qualitative and static quantitative parameters. We are always reminded of one of the biggest financial frauds committed in Asia in recent memory – Satyam Computers in India – a revelation which came about voluntarily three months after the company proudly accepted the Golden Peacock Global Award for Excellence in Corporate Governance. The company basically knew how to game the system (which the auditors did not catch) and the financial community just lapped up the consistency of good numbers dished out by the company without questioning how a mid-sized company could deliver returns better than best in class without any differentiated competitive advantage.

Asian Governance: Independent Studies

Over the last two decades, Asia has gone through its own cycle of governance changes. The shock of the Asian Financial Crisis and the subsequent investor apathy forced a lot of structural improvements in regulation, management structures and investor protection. Asia Corporate Governance Association (ACGA) in collaboration with financial research house CLSA has been doing independent studies on governance in Asia since 2001. The chart alongside from ACGA studies shows that percentage compliance with contemporary best practices in governance has been improving in Asia. In the 2016 survey, Australian companies stood out with a score of 78, followed by Singapore/ Hong Kong in mid-60’s while Indonesia/ Philippines made the bottom with scores below 40.

Corporate Landscape in Asia

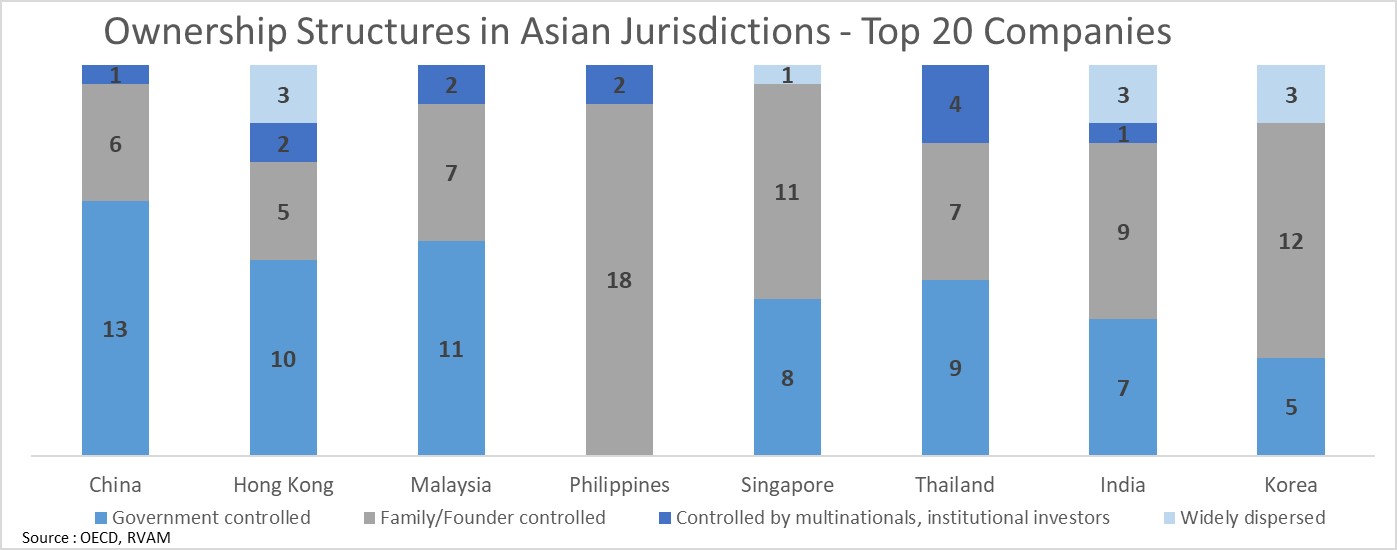

Corporate governance works best when ownership is diffuse and management is professional. However, many Asian companies remain controlled by powerful families, giant parent conglomerates or state actors. Sometimes outsiders get meaningful vetoes as, for instance, minority shareholders in Hong Kong have for related-party transactions. The fact that shareholding is concentrated with management in itself does not imply poor governance, as often the alignment of the return objectives of management and minority investors can produce a great business delivering strong long term returns to all stakeholders. The chart on the left shows the types of control/ ownership structures of the twenty largest companies in various Asian countries.

As Asia continues to grow faster than the rest of the world, the importance of Asian companies in the global landscape continues to grow. Of the Forbes 2000 list of large global corporates, nearly a third (649) is in Asia and this list is growing. But a significant proportion of these companies have some form of state ownership as shown in a recent OECD analysis paper (table below).

In most Asian countries, the state has played a significant role in nurturing the corporate sector in the initial growth years as lack of significant resources with the private sector necessitated the intervention of the government. As countries prospered and developed, pools of savings grew and became accessible to the private sector, so the role of the state has been diminishing in many of them (like Singapore and India). Investors generally tend to stereotype all SOE’s (state owned enterprises with dominant government ownership) as poor in governance with low return potential. This scepticism is understandable as the dominant priority of the state is to provide welfare to its citizens and not maximize shareholder return.

At RVAM, we approach each investment idea with an open mind as, in certain mature industries like utilities, an SOE may be a good investment idea as state ownership gives certainty to the regulatory environment and reliability to accounting statements. If the objective of the dominant owner is stability and reliable operations, with excess cash being paid to all stakeholders in the form of dividends, that is a cashflow stream which has low risk and can be valued using an appropriate discount rate to get comfortable with the investment merits and return potential of the opportunity.

Coming back to the issue of the recent trend among Chinese SOE’s to incorporate the communist party into their articles of association, we view this as part of doing regular business in China. To the western eye the act itself seems alarming, given the very different political and legal systems in most other parts of the world. In China, the differentiation between the party and state is one of semantics. De-facto they are the same. But when something which is de-facto, ends up being de-jure in a Western legal system, it raises governance flags but that is because a different system is being used to evaluate it.

Role of the Dominant Shareholder in Asia

Unlike the developed markets of USA or Europe, in Asia, in addition to the government, the role of the founding family continues to linger in many private sector enterprises. Some of the most successful companies in Taiwan, Asean and India continue to be run by families of the founder and have high standards of governance and consistently generate good return for all stakeholders. We find that successful ones are those which have institutionalized management structure and put in place robust succession planning and a fair governance framework. The exception to this is South Korea.

In Asia, stocks listed in the South Korean stock exchange generally trade at lower valuations when compared to similar peers in other markets, a phenomenon described as the “Korea Discount”. This is due to governance concerns brought about by the dominance of family-run “chaebols” controlling these companies through multiple cross-holdings, with scant regard for minority investors. As investors, we are wary of buying a company in South Korea for its underlying businesses as free cashflow generated by the company, instead of being paid out to shareholders, may end up getting invested in an unrelated business controlled by the same chaebol, thus destroying long term returns for all stakeholders.

Samsung Electronics, the largest listed company in South Korea, is a well-respected global brand, churns out great products and makes good returns on its business, but has historically traded cheap and at a discount to peers. Despite institutions owning 65% of the company and the founding family owning only 15% directly, the company has a very opaque governance structure with control exercised through a maze of cross-holdings among group companies which form part of the Samsung chaebol. The group has been under pressure over the last few years from the government and various stakeholders to change and put in place a more transparent governance structure. The company, for the first time last year, instituted a transparent and fair policy on distribution of cash flows to shareholders. We have been following it with interest as clarity in cash distribution satisfies one of our key criteria on return visibility, but there are still uncertainties about management structure and the future direction of the group structure which increases the risk premium attached to the company. The incarceration of the Vice-Chairman last week (without getting into the legal, political and moral aspects of the case) brings to the forefront this lack of visibility on management direction for a collection of businesses which, no doubt, are world-beaters. A great business with questionable investment merits can one day turn into a great investment if proper governance structures are put in place which align the interest of all stakeholders. We will keep watching this space.

Infosys, unlike many Asian companies, is unique in that it is run by a professional management, controlled by an independent board and has had a historically strong corporate governance culture. It competes with best-in-class global companies in the IT services sector and generates 88% of its revenues from global customers in the US and Europe. Last month the stock took a significant hit as a simmering board struggle spilled out into the open, resulting in resignation of the CEO and quite a few board members, giving speculators a field day trying to find the most outlandish conspiracy to describe the turn of events, which can best be described as a tussle between Frenemies (the outgoing CEO Vishal Sikka and one of the founding promoters, Narayana Murthy who appointed him in the first place). The minor transgressions and accusations were just a distraction from the big picture issue of culture clash, a conservative culture and worth ethic instilled by the founders coming under pressure from a new CEO who was trying to dramatically change the direction of the company and its employees’ outlook and get them ready to take on challenges of an evolving technological landscape. For a company with professional depth and strong governance structure, the distraction was an opportunity which quickly steadied itself the moment a highly regarded ex-employee, Nandan Nilekani, came on board as Chairman with a mandate to look into grievances and put in place a new management team which can deliver on heightened investor expectations.

The Red Flags

One of the areas which we pay close attention to in Asia is related party transactions. Over the years, most Asian countries have put in place reasonable reporting requirements for related party transactions. We do not approach related party transactions with any bias as in many Asian countries the eco-system of related suppliers provides a comparative advantage and entry barrier to competition (for example the Japanese just-in-time manufacturing linkages), thereby enhancing value of a business. However, many frauds and governance problems are easier to hide in related party transactions. To us there is no substitute for meeting managements, asking questions and “kicking the tyres”. A story which is too good to be true may either not be real or the risk too high, so that it would be wiser to let go of the return.

Governance issues are nuanced in Asia. The key is also to understand whether management has the right cost of capital in mind. Often businesses are built not to add value but to meet other objectives, perhaps support growth or jobs in the case of an SOE or build an empire in the case of a family-owned conglomerate. Companies may have the right board structure, governance mechanisms and remuneration policies but may falter at the basic tenet of value creation or using the right cost of capital to evaluate investment decisions. This impacts the future cash generating ability of the company and/or increases the riskiness of cash returning back from the company, thereby reducing the value of the business to an external investor.

At RVAM we always keep our core objective in mind – to protect capital and earn a reasonable return without taking unrequired risk. There are plenty of opportunities available given the robust growth environment in Asia. We can afford to be selective. We do not need to own everything in the market place. Sometimes we let go of good return opportunities because we are not sure of the risk. We are happy to sit out and wait rather than try to wade into a governance situation which cannot be evaluated logically within our risk/ return framework.

End

Disclaimer

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither its accuracy and completeness, nor the opinions based thereon are guaranteed. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This information is directed at accredited investors and institutional investors only.