As any society becomes wealthier, there are certain demographic changes that happen inevitably. Fewer marriages take place, some of the marriages that do take place, happen later, which in turn inevitably leads to fewer kids. This has a profound impact on the labour force as the working age population starts shrinking. This, if not supported by improving labour productivity and participation, inevitably leads to a sharp slowdown in growth. Immigration helps postpone this indefinitely, but then a lot of countries are not natural immigration destinations.

China is going through this exact process but at a much faster pace. This amplification is because of its much faster pace of wealth creation and uniquely because of its one-child policy. Hence the oft repeated phrase, “China is becoming old before it becomes rich”.

The market implications of these trends are multi-fold. Firstly, this demographic trend gives a deeper insight into some of the regulatory changes that are happening now. Once the impact of this trend is better understood, the regulatory changes seem less erratic and more coherent. The second market impact is the change in sectoral winners and losers as this demographic change continues. Broadly, a sector selling to the young (defined as younger than 45 years of age) will struggle to match the growth of the past twenty years. On the other hand, sectors selling to the older generations, smaller households, singles, etc. will benefit. The market is slowly recognising this, but the true differentiation will show up only over the longer term.

The Demographic Shift: Dropping Birth Rate and a Rapidly Aging Society

Fast Dropping Births

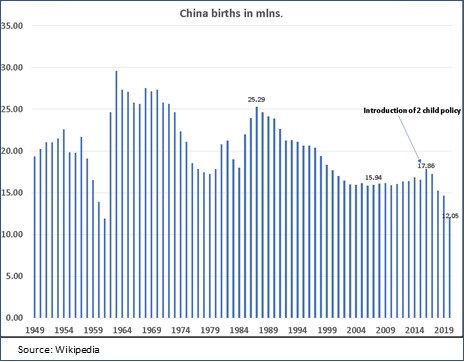

China’s birth rate has been sharply dropping. It’s one child policy was introduced in 1979-80 and the impact slowly filtered in over the next 5-7 years (with a relaxation in 1985 for rural residents if the first child was a girl). It is believed this led to a potential reduction in births of over 400 mln Chinese over 40+ years. In 1987, the number of births peaked at 24 mln. and went down to about 16 mln in 2015 when the policy was relaxed to allow two children. There was slight bump up in births to 18mln. in 2016 but that has sharply dropped to only 12 mln. in 2020 (though admittedly partly because of temporary COVID-19 related reasons). This has led to the relaxation to a three-child policy as announced in the middle of 2021. Most people, however, believe that this, like the two-child policy, will have an immaterial impact on the birth rate.

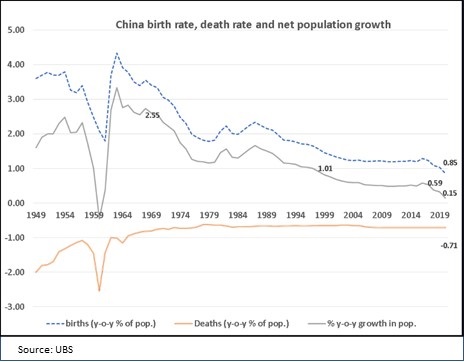

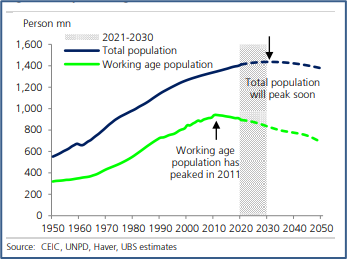

This dropping birth rate combined with a steady death rate of about 0.7% of the population every year is leading to a sharp slowdown in population growth. In 2020, the Chinese population grew at barely 0.15%. This number was 1% in 1997 and 0.5% in 2015. China’s total population is expected to peak somewhere in the middle of the coming decade. That explains the government’s sudden increased focus on boosting child births primarily through reducing the cost of bringing up a child.

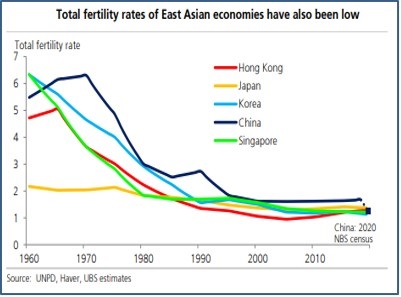

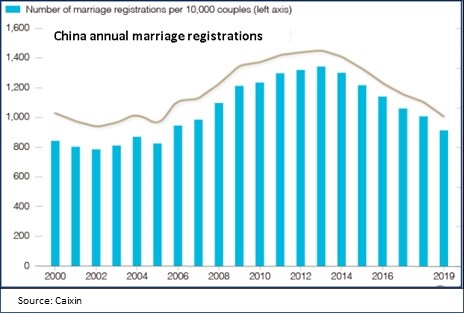

This trend unfortunately is expected to continue and is very difficult to reverse. If one were to look at factors like marriages and fertility rates, both point to further shrinkage in annual births. China’s fertility rate has now gone below 1.5% (in 2020 it was only 1.3%), and this is way below the neutral rate of 2.1%. On the marriage front also, the numbers are shrinking fast. From a peak of over 13 mln. marriages in 2013, the number has dropped to only about 8 mln. in 2020. This is a simple but accurate predictor of future birth rates.

Rapidly Aging Society

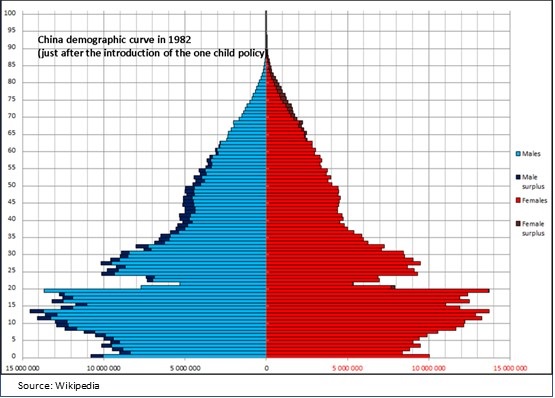

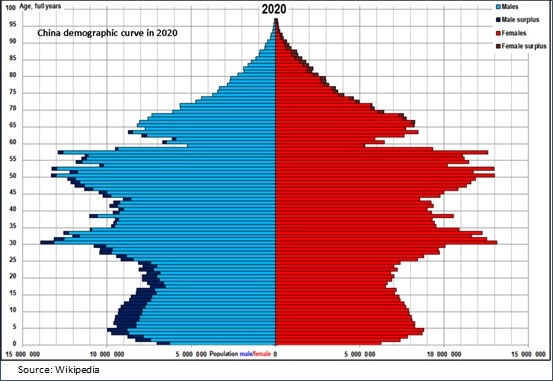

The first impact of the sharply slowing birth rate is on how fast Chinese society is aging. The figures below compare the population spreads across age groups in 1982 (just as the effects the one child policy started being felt) and in 2020. Clearly the “bulge” has moved from the 10-20 age group to the 45-55 age group over this 38-year period. This latter bulge represents the kids born in the 1962-1972 timeframe. This was the high birth rate which led to the one child policy. This cohort is now heading into retirement age. Remember, the Chinese official retirement age is 55 years for women and 60 for men. As this cohort ages and birth rates continue to drop, the Chinese average age will rise rapidly. The society will look a lot like those of Japan and Korea but potentially much before China reaches the per capita wealth of these countries.

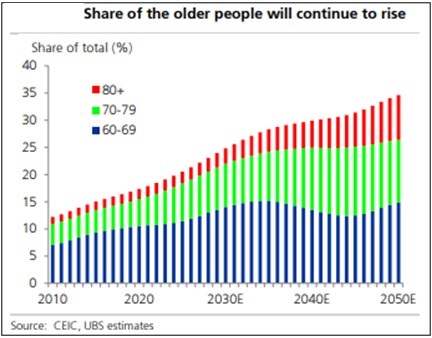

The proportion of the population over 60 years of age has moved from 12% in 2010 to 18% in 2020 and is expected to be 25% by 2030 and over 35% by 2050. Remember, for Japan, people over 60 years of age hit 25% of the population only in about 2010. Japan had a per capita GDP of USD 45,000 then. If China hits that milestone in 2030, it will have a per capita GDP of only about USD 20,000 then. Hence the phrase ‘growing old before growing rich’. We believe that within the next fifteen years, the investment world could look at China as it looks at Japan now – steady, low growth, high tech and with surplus savings.

The Shrinkage of the Labour Pool

The second impact of the demographic changes is in how Chinese society is re-organising itself. The number of singles is growing fast, families are becoming more nuclear and smaller, divorce rates are shooting up, second marriages are more common (25% of people marrying in 2020 were doing it a second time, compared to 11% in 2013), education levels are going up, etc. But the biggest change is clearly felt through the shrinking working age population. Chinese working age population peaked in 2011 and has shrunk by 40 mln. since then. This is expected to shrink a further 60 mln. in the next ten years. This is like taking away half of America’s working age population over a 20-year period. This has huge repercussion for China for sure but also for the rest of the world. The world since 2001 has benefited from the deflationary impact of a large, productive and very cheap work force entering the global economy – this is when China entered the WTO. This impact is reversing and hence will become an inflationary force which the world might not be ready for.

For China, there are ways to reduce the impact of this demographic trend. One obvious answer is to increase the retirement age. The Chinese retirement age (55 years for women and 60 for men) is too low. With improved health care, the retirement age can easily be increased by over five years as is being done in countries like Japan and Singapore. The second way is to improve productivity. Increasing training/ education is an obvious answer. China is considering raising compulsory education from the current 9 years to 12 years. Also, there is clearly an increasing focus on vocational training, mid-career training, etc. Historically, Chinese labour productivity has also benefited from the migration of labour from farm labour to urban labour. But this process is running out as already 75-85% of the Chinese work force is now urban.

Connecting Some of the Regulatory Changes to this Demographic Trend

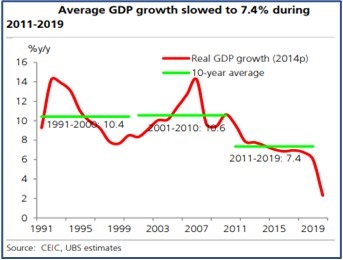

One of the obvious conclusions from this demographic change is that future structural growth is notching down. From a growth rate of over 10% per annum over the 1990-2010 period, growth has slowed down to 7.4% p.a. over the 2011-2019 period. The expected growth over the 2019-2030 period is probably going to be nearer the 5% mark (assuming no big mishap). The Chinese government realises this. But this creates a problem as it shakes the social compact between the Chinese people and the CCP (the Chinese communist party). The compact was – “the party gives the people economic growth and people give up some of their freedom to the party”. But as economic growth slows from 10% to 5% within a 20-year period, for large parts of China it would feel like no growth. This may lead to the rise of a large underclass with a strong sense of betrayal.

Once we understand this, the current policies of the CCP are easier to decipher. When you cannot get enough growth to keep even the poorest happy with the trickle-down effect, then you need to start focusing on redistribution. This leads to the oft-repeated term coined by Xi Jinping – “Common Prosperity”. In simple terms it just means a more populist move to redistribute wealth from the top to the lower economic classes. The obvious loser is the owner of capital. Even China’s increasing nationalism and seemingly increasing antipathy towards capitalists can be cynically viewed as a way to distract from the slowing growth and weakening social compact.

These regulatory changes in mindset have already manifested in various ways. The bringing down of the billionaire class is a clear public statement that this redistribution has started. The focus on cost of education, housing, etc. points to an effort to reduce the cost of living for younger people and to encourage a higher birth rate. A focus on the environment is also a move to reduce focus on growth and increase focus on social good. Even the higher focus on data security, antipathy towards foreign investors, etc. could reflect a willingness to reduce focus on growth to achieve stability and redistribution.

The Losers and the Winners

Through all this there will clearly be losers and winners. Even at a growth rate of 5% p.a. China will add more than 3 Indias (of 2019) to its GDP over the coming decade. This is adding over USD 9 trln. to its current GDP of USD 15 trln. This is a lot of wealth creation for investors to participate in. The only point is that the industries for investors to participate through might be different from those of the past ten years.

One important impact of this demographic change will be the reduced competitiveness of various industries in China, especially the ones in basic manufacturing. This will create increased opportunities for markets like Asean (especially Indonesia and Vietnam), South Asia, etc. Also, the Chinese economic mix will move to industries like healthcare, aged care, pet care, higher education, asset management, basic technology, sustainability-focused industries, automation-related businesses, etc. On the other hand, youth- and manpower-focused industries will suffer – for instance baby care, property (as the buying age cohort stops growing), primary education, manpower-intensive online businesses, etc. Overall, the economy will increasingly focus on consumption and less on savings and investment, as is the norm with an aging cohort.

Our job as astute investors will be to continue to focus our portfolio on the industries that will benefit and be wary of the industries that will face headwinds.

End

Disclaimer

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither its accuracy and completeness, nor the opinions based thereon are guaranteed. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This information is directed at accredited investors and institutional investors only.