While the world debates about China growth, crude oil and interest rates, this month we decided to go back to the beaten path of share buy-backs. However, this is not the usual drivel about how share repurchases that improve corporate earnings per share have become a major part of any CEO’s playbook these days. Or a critique that the practice is no more than financial engineering that comes at the expense of reinvesting in the business that can come to hurt a company’s long-term growth prospects.

This is about a book called “The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success”, which we came upon recently, written by William N Thorndike, Jr, the founder of Boston-based private equity firm Housatonic Partners, which manages $1 billion in assets. A perusal of the book’s preface triggered off the thoughts mentioned in this month’s newsletter.

The author of the book researched a large number of CEOs over eight years, finally writing about only eight in the book. Thorndike concludes that to achieve meaningful outperformance, CEOs need to do things differently from their peers in their respective industries. He says, “Over a long period of time CEOs have to do two things well: they have to manage the business to optimize the profits and after that deploy the profits. Most of what separated these guys from their peers is in the second activity, we commonly refer to as capital allocation.” He also found that the CEOs he researched had quite a bit in common. They also bought back a lot of stock.

He noticed that these were not just regular corporate’ buy-backers’. These guys were not mindlessly repurchasing shares each quarter once their boards approved them. They gave buybacks deeper thought and executed them quite differently from the way other companies did or do even today. Unlike many publicly-traded companies today, they did not announce big stock buyback authorizations and repurchase a systematic amount of stock every quarter. Instead, Thorndike’s CEOs waited for long periods of time and, when they thought their stock was cheap, they moved in and scooped up the stock in large quantities. “They had the investor’s mind set,” says Thorndike. “They viewed it as an investment and when it had attractive returns they did a lot of it.”

Over time, the share count of these companies shrunk rapidly and drove EPS growth faster than it would have purely organically. Result; outsized stock outperformance a.k.a. shareholder returns over an elongated time frame.

The above is very important and fundamental to the way we think about companies at River Valley Asset Management. As investors, people tend to want growth in all things, from corporate earnings to same store sales to overall GDP and everything in between. We believe growth isn’t everything. There are any number of less-known companies whose sales or profits have not grown as fast as one might imagine but whose total shareholder returns over long periods of time have outpaced those of

their peers. Returns can come from 1) growth in earnings, 2) change in valuation and 3) return of capital to shareholders through dividends and buybacks. Companies can grow earnings but their P/E ratio often remains the same years later. What one finds is that the major source of returns has been dividends and buybacks, which have significantly affected earnings per share. While earnings may have grown, the EPS grew faster due to the buyback effect. However, does this translate into total

returns that exceed the return of the S&P 500?

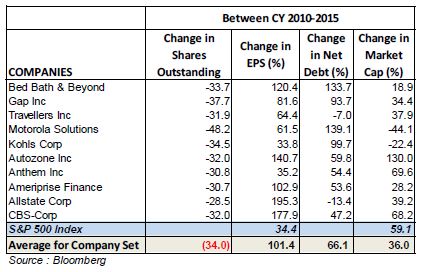

We put this to the test and ran a screen on Bloomberg that sought out companies with market capitalisation greater than US$5bn in 2010 which had seen a reduction in share count of more than 20% between 2010 and 2015. We took the top ten names showing the maximum decline in share count over this period (i.e. largest executers of share buybacks) and then ran a simple average of their EPS growth, total stock returns and change in market capitalisation between 2010 and 2015. We then compared this against the returns and change delivered by the S&P 500 during the same period.

The results were not quite what one would imagine. These top ten companies registered a reduction in their share count of a whopping 34% between 2010 and 2015. During this period their average EPS grew by 101%. Their net debt galloped upwards by 66% resulting in a market capitalisation change of 36% for the whole set.

The humble S&P 500 in the same time frame, delivered an EPS growth of 34%, but its market cap grew by 59% during the same period. Clearly our top ten share buy-backers under-performed badly. The short summary is that buying back large amounts of your own company’s shares does not guarantee that shareholder returns will be created in the long term. Further, while share buybacks elevated EPS growth substantially, they do not necessarily translate into shareholder value growth in excess of the S&P 500’s own growth (excluding dividends re-invested basis) over a similar time frame.

There could be multiple reasons to explain the above under-performance in this particular set – external factors, internal execution of the buybacks themselves, the loading up of debt to affect the buybacks, etc. The bottom line is that share buybacks are not a panacea or a substitute to deliver EPS growth singularly.

The important lesson to learn is, as Thorndike points out, that when buybacks are funded mostly through internal accruals i.e. free cash flows, and performed when stock prices are cheap, their potency improves sharply and even magnifies the effect when executed over a long time frame.

End

Disclaimer

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither its accuracy and completeness, nor the opinions based thereon are guaranteed. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This information is directed at accredited investors and institutional investors only.