As we close the first half of the year, we have just finished a slew of elections in Asia with results broadly in line with expectations, making us ponder the opportunities presented to investors by the outcomes. As North Asia gets mired in trying to figure out Trump and what he wants to do next with China or North Korea, the Southern part of Asia is providing a refreshingly different picture. By voting for continuity and stability over the next five years, whether in Thailand, Indonesia or India, the potential exists for a new investment narrative to emerge in this part of Asia.

Earlier in the year we wrote about the opportunities we see in Indonesia, but investors keep asking us “What about in India?” Now this is a tougher question to deal with, given the diversity of opportunities in India on the one hand weighed against the conundrum of rich valuations and the imponderables of a tough macroeconomic backdrop.

The Southern Asian Landscape

Before we delve deeper into the Indian opportunity, it would be good to consider what five years of stability could mean for the investment landscape in countries which just finished their election cycles. Asean and India combined will have an estimated GDP of close to $6tr this year growing at the rate of 5-6% p.a., a sizable block in its own right, a little less than half the size of China which is estimated to be around $13-14tr. If we go back in time, China was an approximately $6tr economy in 2010, less than a decade back. It invested a lot in infrastructure and grew its manufacturing base to reach its current size. The logical question to ruminate on is whether the southern part of Asia can follow a similar path.

In terms of infrastructure, if we look at the largest economies in the region, there is room for optimism. India’s newly elected government run by the BJP has promised in its election manifesto an investment of $1.5tr into infrastructure over the next five years. In Indonesia, the Strategic Projects Program envisages an investment of $300bn, while in Thailand the government is focussed on the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) for which investment commitments of $30bn have been made with another $20bn in the pipeline. Even if not all of the plans fructify, at least the intent exists, which could very well become a significant growth driver for the region in the near future.

On the other hand, the region has got mired in the current mood of gloom as Trump’s tariff tirade on China has raised questions about the sustainability of the Asian export model. When we talk to corporates in the region, irrespective of the outcome of the US-China relationship, most of them feel that they need to have a de-risked manufacturing strategy, which is translating into a hunt for alternate manufacturing locations for global sourcing. The good news is that most of the locations being considered are in this part of the world, whether they be Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam or Indonesia and in some cases even India.

Whether the stars get aligned or not, only time will tell. But clearly we see potential for a new emerging story in Southern Asia (Asean plus India), with growth driven by investment and manufacturing and not just consumption which has been the traditional driver.

The Indian Opportunity

The long drawn out parliamentary elections in India got over in the month of May, bringing the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi back for another five year term (dubbed Modi 2.0 in popular narrative). The surprisingly strong mandate has given rise to aspirations that perhaps the next five years could deliver on the unfinished agenda from the previous term. Understanding the challenges faced in the first term, the changes brought about and their implications are key to evaluating the potential opportunity set for investors to generate returns from India over the next five years.

The First Term of Modi

Five years back the election of Modi heralded a paradigm shift in India, an economy which at that time was mired in inflation. The electorate, fed up with crony capitalism, voted for change. Most observers give credit to the government for bringing about transparency in decision making, controlling inflation, investing in infrastructure, tacking corruption head on and instituting the long debated Goods and Services Tax, which moved the economy to a single common market. While the changes were structurally positive and underpinned the long term growth of the economy, in the short term the corporate sector in India was getting bogged down by the legacy of crony capitalism and the lack of resources to kick start an investment cycle.

As the then Chief Economic Advisor to the government observed, India for many years practised “socialism with no entry” and in the last two decades with the opening up of the economy, it ended up with a regime of “capitalism with no exit”. Both these regimes favoured crony capitalism but of different varieties. The end result in either case was a banking system saddled with non-performing assets that were not getting resolved, thus freezing up capital which could have been used productively in the economy. The introduction of the Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code (IBC) in 2016 is, we think, the biggest achievement of Modi 1.0 as it moved the country to a time-bound, rules based system for resolution of corporate distress.

Investment Themes for Modi 2.0

As we explore the Indian equity market to find new ideas to ride continuity and the second wave of the Modi government, what stands out are the high valuations underpinning corporate India which is struggling to deliver on earnings expectations. But there are pockets where improvement in fundamentals is being overlooked due to historic baggage. One such segment of the market is Public Sector Undertakings (PSU). We are not fans of PSU’s most of the time as the management incentive structures are never clear and that impacts shareholder value creation. However there are fundamental changes taking place in the corporate landscape in India due to IBC implementation. The relationship between PSU banks and corporate India is changing for the better in favour of the former.

The IBC has brought about a change in corporate behaviour as increasingly managements realize that if debt is not serviced properly, they could lose control of their companies. As more and more cases get resolved in a timely manner under IBC, banks are also getting comfortable in using this powerful legislation to unclog their books. A total of 1,858 cases have been admitted for resolution under IBC of which nearly 38% (715) have been resolved as of March 2019. Banks and financial institutions are expected to realise more than $12bn in 2019-20 from resolution of stressed assets under the IBC as compared to $9.4bn realized in the previous fiscal, as per rating agency ICRA. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in its recently released financial stability report forecast that non-performing assets of PSU banks, after peaking at 15% in March 2018, are expected to fall to 12% in March 2020. Clearly we are seeing a trend of improving balance sheets for banks in India as a result of IBC implementation.

Inflection points are always a good time to look for ideas which the market has forgotten, especially when one is in the midst of a fundamental turning point as is the case with corporate lenders in India. Doing deep dive research, we came across one entity – Bank of Baroda – where valuations are not capturing the fundamental shift going on in the environment.

Bank of Baroda (BOB)

BOB is the third largest bank in India after SBI and HDFC Bank. As a state-owned (PSU) corporate bank, it normally escapes the attention of most investors, but changes in management over the last couple of years, followed by a clean-up of the books courtesy of the IBC, combined with a recent merger with two other PSU banks has given it the size, scale and ability to become a large and reasonably profitable bank in India. And when we look at the valuation at which the bank is trading, we clearly see a good investment opportunity waiting to be discovered.

Understanding the Investment Case

BOB is a strong franchise but was run as any other typical PSU, with hardly any differentiation, lending predominantly to corporates, which resulted in the asset quality problems it found itself in just like the other PSU banks where the government is the largest stakeholder. Things started changing in the middle of Modi 1.0, when BOB was considered a forerunner for reform of PSU banks. A new management team from the private sector was brought in with Mr. PS Jayakumar, an ex-Citibanker, appointed as CEO and Mr. Ravi Venkatesan, ex-chairman of Microsoft India, appointed as Chairman. The initial excitement was soon overtaken by the hard reality of having to change decades of organizational sclerosis and bureaucratic procedures. The impatient market did not have the patience to wait for the results of the experiment to claim the veritable pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

But time heals and things change. Taking tough decisions on asset quality, bringing in outside talent, changing the work culture, changing the focus to new business lines all took time but the results started to show a year or so back. Other than operational efficiency, the biggest transformation that took place was the growth and development of a parallel business line – retail lending – akin to what successful private banks in India have built their business models around. Given the strong middle class franchise that BOB had, it was always a mystery why they did not have a strong housing finance book. What retail banking required were different systems and processes for decision making, monitoring and collection. And that is exactly what the new management team put in place. The results are now visible for the market to grudgingly start giving credit.

But time heals and things change. Taking tough decisions on asset quality, bringing in outside talent, changing the work culture, changing the focus to new business lines all took time but the results started to show a year or so back. Other than operational efficiency, the biggest transformation that took place was the growth and development of a parallel business line – retail lending – akin to what successful private banks in India have built their business models around. Given the strong middle class franchise that BOB had, it was always a mystery why they did not have a strong housing finance book. What retail banking required were different systems and processes for decision making, monitoring and collection. And that is exactly what the new management team put in place. The results are now visible for the market to grudgingly start giving credit.

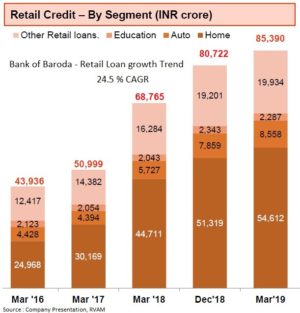

The chart alongside shows the trend in retail loans for BOB, growing at a rate of 24.5% p.a. over the last three years. This was achieved during a period when system loan growth in India was running at a 10-12% range while BOB itself grew lending at a 7% CAGR.

The Next Googly

This being cricket season (with the ICC Cricket World Cup 2019 tournament going on in England), we thought the best way to describe the surprise sprung on markets a little over nine months back as a “googly”. Just as the market was warming up to the transformational success, the government announced the merger of BOB with two other PSU banks, Vijaya Bank and Dena Bank. The first reaction – and rightly so – of the market was “there goes the transformation story; we are back to BOB being another PSU bank”.

The two new entities, Vijaya Bank and Dena Bank, presented a mixed picture. The former was a predominantly South Indian bank with a good franchise and balance sheet but meagre growth and an under-provisioned balance sheet, while Dena Bank was a badly run corporate bank with weak systems and problem assets bad enough to wipe out the equity base. The unknown problems of the latter were a genuine worry for the market. The uncertainty was offset by a number of significant facts: a) the merger was taking place at the end of the asset quality deterioration cycle in India, thereby providing all stakeholders enough data and visibility to properly recognise the problems and value the respective entities, and b) the government provided the entities close to $1.4bn of capital to clean up the books pre-merger and start on a clean slate. In the process the government took a nearly 50% haircut on its capital injection into Dena Bank to ensure that the merger went ahead.

Back to the Future

Life is never like the American Science fiction movie “Back to the Future”. We can always wish to go back in time and change something to make our present different and the market as of now seems to be in no man’s land with the merger of BOB. But it does not require rocket science to go back and pick up the balance sheets and put together a picture of what the future of the new entity will look like, with some reasonable assumptions. What we see is something that could pleasantly surprise the market. The merged BOB will be the third largest bank in India with most of the problems assets turning a corner, with a reasonable level of capital and core profitability (as measured by pre-provision operating profit – PPOP) for it to execute on the original vision of a balanced, steadily growing BOB. And from an investors perspective this new entity is trading at a discount of 35% to its new book value.

There are always issues with management execution in any entity and only time will tell how the future shapes up, but given the recent track record of BOB management in turning around an old franchise, we think their ability to integrate the new entities and give them direction is worth betting on. And what helps here is the franchise, which is now large and powerful, which cannot be ignored at the current valuation of the third largest bank in India.

End

Disclaimer

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither its accuracy and completeness, nor the opinions based thereon are guaranteed. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This information is directed at accredited investors and institutional investors only.