In last month’s newsletter, “The Changing Normal”, we reminded investors of how ‘value’ stocks have abounded in Asia and possible reasons for them being out of favour with investors. This month we delve a bit deeper into this rather contentious topic knowing that it is one that can never possibly unite all kinds of investors.

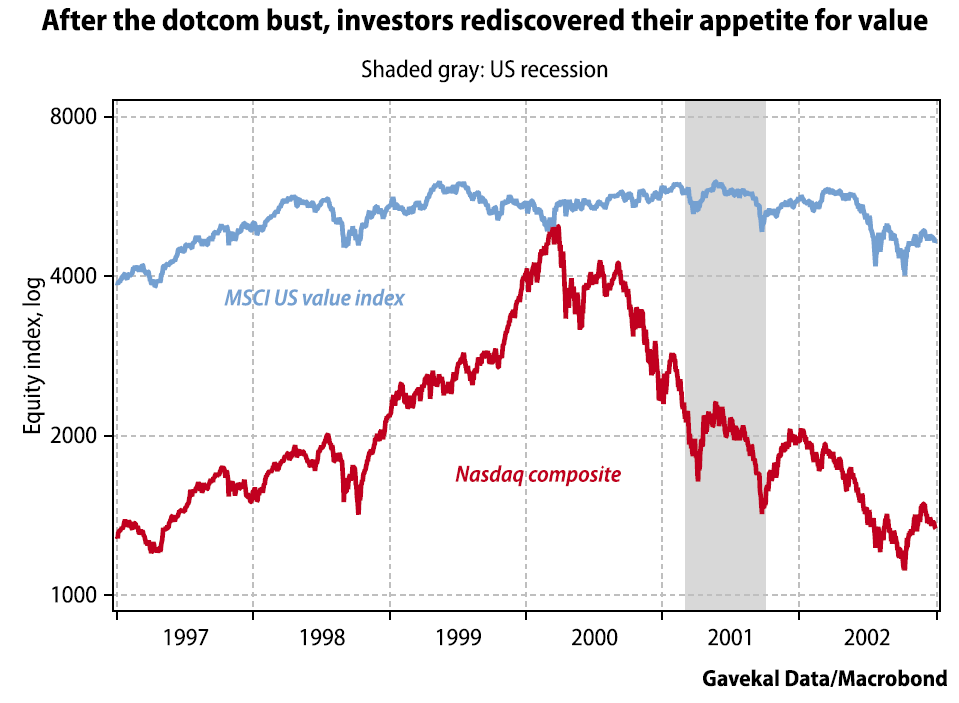

Value investing has been declared dead several times in the past. It is being declared dead yet again. However, no style of investing dies; it just passes through long fallow periods. Value investing has done that several times in history, most notably in the ’60s when the likes of Xerox, IBM and Eastman Kodak were the darlings of investors and then in the 1990s dot.com or tech bubble, with its own Cisco, WorldCom and AOLs among others that relegated the traditional blue chips to the garbage heap.

While the style never really dies, what has happened in this past decadal bull market in the U.S. especially, is that the value-oriented approach has adapted and adopted alternative metrics to include the increasing intangible assets of a company’s operations. Sadly, accounting hasn’t kept up with this rapid change of valuing businesses to include these appropriately.

The most oversimplification of what value investing is, is trying to buy what’s worth a dollar for 75 cents. On the other hand, an equal oversimplification of what growth investing is, would be that it’s buying something valued at 75 cents for a dollar with the expectation that it would be valued at way more than 75 cents over time.

We could argue that both approaches are “value investing.” The difference is that in the latter, investors are valuing the probabilities and possibilities of the future of the company more than the realities of its possibly glorious past. Effectively they take the risk of their assumptions proving to be optimistic or even exaggerated and hence not paying off. One of the fundamental truths we must accept as to why the growth camp has won hands down over this decade is that growth investors have earned their outperformance as a result of their willingness to take on that risk. This is visible in stock after stock that claim to be the poster boys of this decade’s fantastic bull market. To illustrate this point let us take the following example.

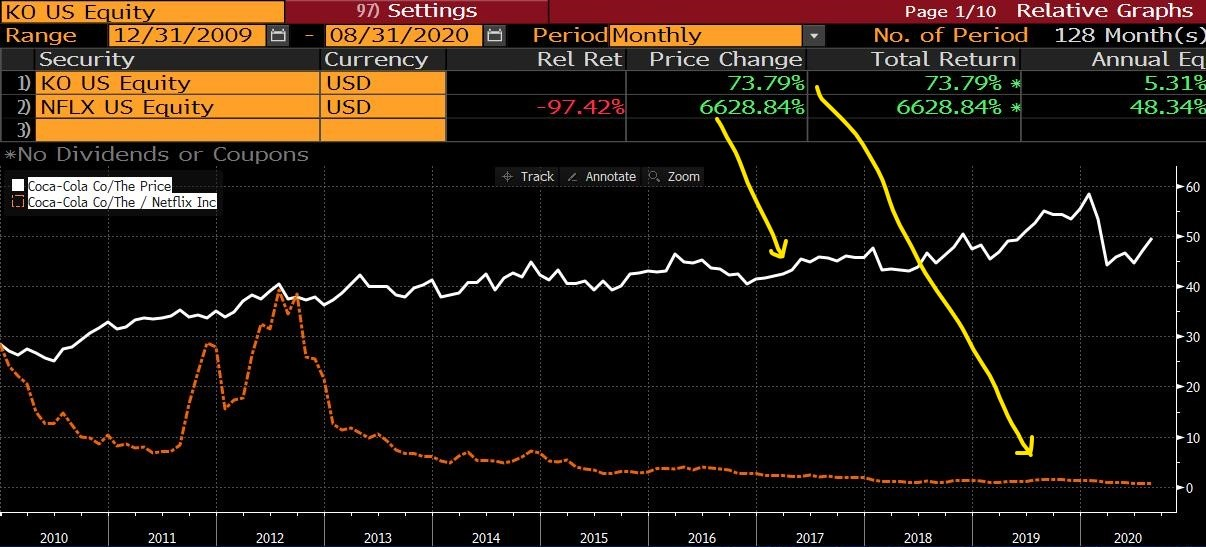

It was low risk to invest in Coke ten years ago because we knew that people wouldn’t ever stop drinking Coca Cola; possibly, more would be drunk with the population growth in developing economies where Coke was spreading its reach further and deeper. It ticked every box that a good long-term investment ought to. On the other hand, it was a much higher risk proposition to invest in Netflix ten years ago, and to bet that it would succeed against all odds, faced as it was with entrenched media models that seemingly looked impregnable.

Netflix went it alone, building a standalone video streaming platform (just when the mobile and social media phenom were coming into their own), produced original content, bolted on regional flavours and built an audience not just at home but globally. Advances in mobile phones and tablet technology around the same time weren’t coincidental. Very soon, streaming video content of every kind became the norm rather than the exception, leaving traditional modes of entertainment stunned cold with little time to react. Cord-cutting in the U.S., the advent of the cloud and OTTs changed the industry on its head in a matter of a decade.

Note that Netflix investors had few metrics to measure what these changes could amount to in the years ahead. Growth investors who bore the risk of Netflix succeeding through this tumultuous decade have been rewarded well in excess of those who chose to side with trusted Coke, a company that has always had the odds in its favour. Since Jan 1, 2010, the Netflix stock has risen 6,600% against the paltry 74% rise of Coke’s. One could compare any stock with characteristics similar to Coke’s and the disparity in performance would most likely be starkly in favour of Netflix.

Source: Bloomberg

The Netflix investor could rightly claim that he was always a “value” investor and that owning Netflix didn’t change anything as far as his process was concerned. It’s just that what he was valuing wasn’t the legacy of Netflix – which didn’t exist – neither was he bothered about its physical assets or anything else that was part of its tangible book value. All he focused on were things that were not quite part of the investors’ playbook historically. Concepts such as recurring subscriber revenue growth. Or fathoming the future returns on investments made today in original content. And the amount every consumer of Netflix would be willing to pay to watch such diverse content, regardless of language, anywhere on the planet. The fact that there was nobody else doing it gave Netflix free rein to chart its growth trajectory and horizons.

That seemed as exciting or even more than the prospect of evermore people downing Coca Cola over that time. To the Netflix investor, these were some of the metrics that signified value, not the GAAP accounting treatment of goodwill and intangibles being amortised or whether a utility somewhere was being paid as promised and on time or what it did with its working capital. In a sentence, today’s investing mantra then is: everything that counts can’t really be counted.

We know this flies in the face of everything that we learned through reading investment gospels and through our formative years and working careers. Today, everything that’s been happening in financial markets can be described by adjectives such as ‘extraordinary’, ‘incredible’ or even ‘bizarre’. The truth that investors must face up to isn’t an outlandish one: it is that we need to include new and modern measures to value assets and incorporate these concepts just as much, if not more, into our traditional techniques, without necessarily eschewing and jettisoning the old and tested ones.

We understand how abhorrent such an approach to understanding the market may be to some. But even these detractors will silently admit that things haven’t exactly worked out for them using their traditional toolkit. The pandemic has simply accelerated the trends that had been in place even before it came upon us. Low Price to Book or Price to Earnings or Free cash flow yield multiple, pick your favourite ratio and screen of stocks that answered to them. They have not protected the downside to portfolios or provided outperformance when markets have recovered since that fateful crash of March 2020. At least not yet.

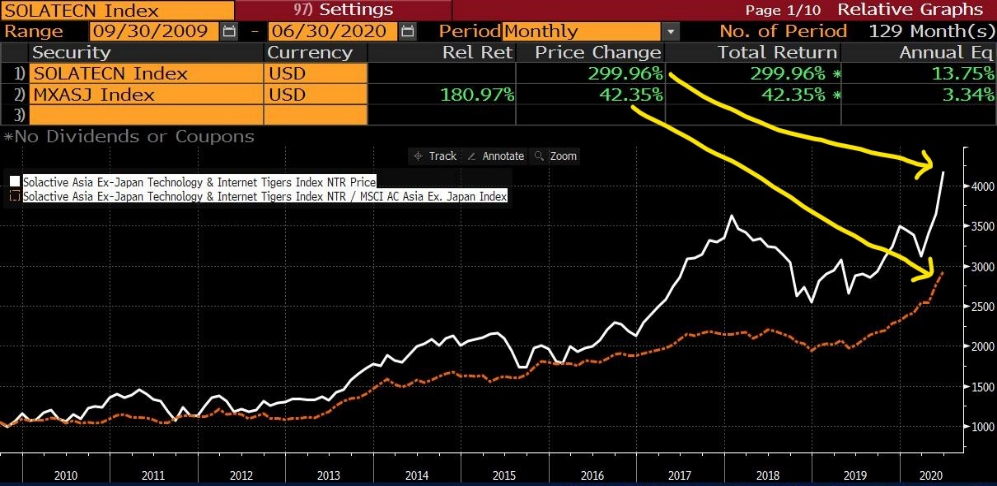

The truth is that the value versus growth swordfight has almost become inconsequential when it comes to measuring investment performance in recent years. It is more appropriate to term it the clash of technology versus the rest. Technologically backed and supported businesses have thrived, making everything around them look plebeian. Asia’s own version of the Nasdaq 100 is a little-known index called Solactive Asia Ex-Japan Technology & Internet Tigers Index NTR, that tracks the leading technology companies resident in this geography and includes names from the vaunted Alibaba, Tencent, Samsung, TSMC, SEA Ltd., JD.com and Infosys to lesser lights such as iQiyi and Momo. This index’s outperformance bludgeons every other index in the geography over any time frame in the past decade.

The question that keeps popping up frequently in our investment meetings and over the evening beer with industry buddies is what will turn the tide for deep value stocks and when. The answer to that question perhaps lies in addressing the reasons why things have come to such a pass for this whole bunch of sectors and stocks, more pertinently in developing Asia and perhaps to a lesser extent in the developed world.

Source: Bloomberg

What Ails The ‘Value’ Universe Today In Asia Ex-Japan?

High economic sensitivity: Today’s ‘value’ stocks are typically mostly economically sensitive. Considering the prolonged period of sub-par global economic growth, it isn’t surprising that such companies have delivered weak growth or declining profits, leading to their stock prices under-performing serially. Now, with a global recession upon us, their recovery has been further stymied and protracted. Until there is a palpable belief that a durable economic recovery is at hand, not just in Asia but globally, it will be tough for investors to warm up to this bunch of stocks with any conviction.

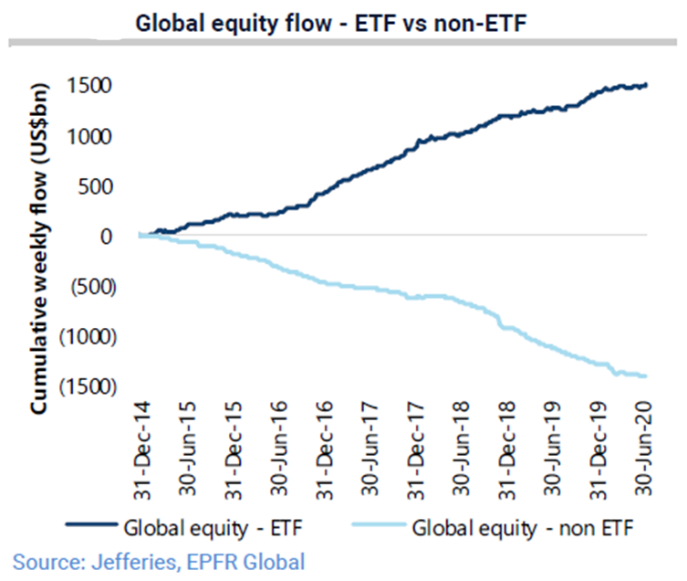

Lower for longer interest rate regime: Last month we alluded to the bane of low interest rates and how it is impacting the investment selection process to the exclusion of certain types of industries and stocks. This oppressive interest rate regime has driven the world into the arms of passive investing through ETFs, causing massive herding by fund managers, index-linked investing and algorithmic trading machines which has reduced the level of decision-making of active managers and capital allocators. Such technical factors remain deeply entrenched. Active managers’ ability and desire to act in a contrarian fashion and seek deep value opportunities has become appreciably feeble as the incentive structure and performance pressures simply don’t allow them any elbow room. As such once again, the linkage to the global interest rate cycle is seemingly inextricable for now.

Poor capital allocation/ ESG issues: There is also the important issue of poor capital allocation, ESG and corporate governance issues, broadly speaking, which has brought about the undoing of several companies in Asia. Some of these were darlings of the previous bull market but which investors, bitten hard by their waywardness, have left adrift. This bunch of companies has a tough job of winning back hearts even if they were to reform themselves on such issues.

SOEs’ apathetic corporate behaviour and compulsions: Asia is also beset by a large number of State-owned enterprises (SOEs), many of which are large behemoths, some virtual monopolies and others which are professionally managed and well-run. Alas, many of them also have social and political obligations to meet, which can be at odds with what the stock market desires.

What precludes these SOEs from becoming favourites is that their political masters fail miserably when it comes to understanding what global investors seek in terms of capital allocation decisions, cash-flow management and distribution, agility in decision making, and technology adoption. All of this has often led to a slow atrophying of their competitive advantages built over many years and, consequently, declining profitability and return ratios – a sure-fire recipe for their stocks to be de-rated in the stock market.

The remedy for such companies is for governments to awaken to their follies and make sure that their interests are aligned with those of minority shareholders to a much larger degree than they are at present. There may be hope yet that such affirmative actions and utterances could bring investors back to considering them investment worthy in future, all else remaining equal.

Looking for Self-Help Cases

Many of the above remedies may take their own time to have an impact. Meanwhile it is possible that one needn’t wait for a broad global economic recovery for the stock market to take notice of the change in fortunes. A company may turn things around for itself against the odds or because it benefits from a turnaround in the fortunes of the country in which the business chiefly operates or the sector itself undergoes a cyclical change for the better.

Chinese and domestic-focussed plays: For example, several Chinese companies are home-grown and dependant on the domestic economy for their growth, even though there may be global cyclical linkages to their businesses. Such companies too have been meted out poor treatment in the stock market thus far. In our opinion, such companies have a better chance of getting back into favour with investors as China charts its own course post the pandemic and these companies figure a way to get back to growing revenues and profits. The caveat is that several of them tend to be SOEs or related to some provincial government entity, where the usual issues surrounding capital allocation/ cash distribution may be bugbears.

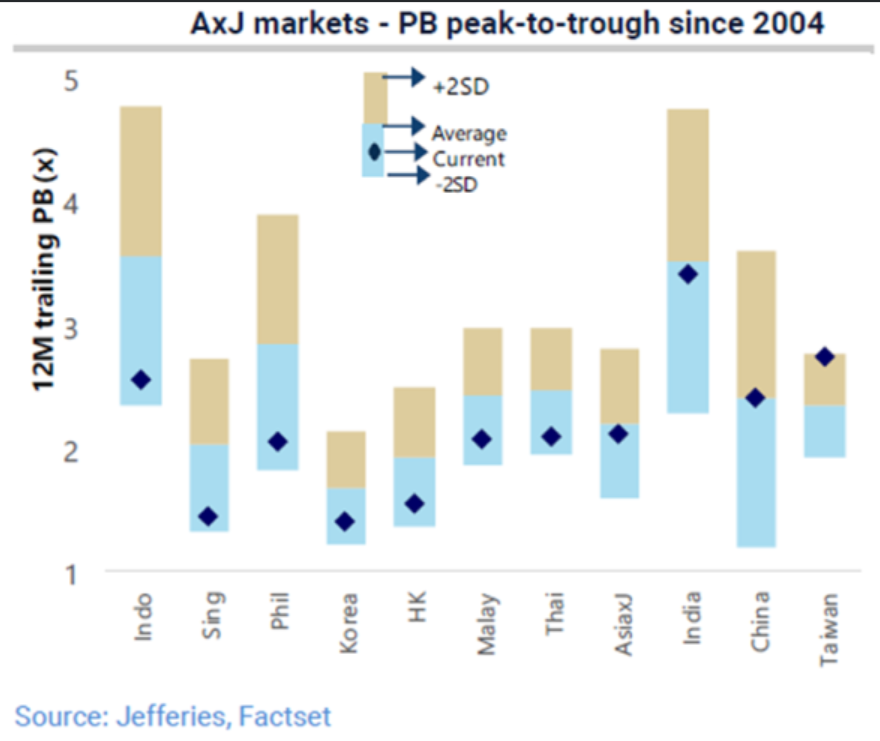

Global Cyclicals: Companies that operate across global commodities (soft and hard), energy, capital goods sectors and financials have the largest share of beaten down stocks today across regions. While there have selectively been some bright sparks, the vast terrain is strewn with companies trading at more than 1 or 2 SD below their long term mean valuations.

The ‘Funky’ Bunch: The final category of value stocks is that bunch of perfectly strong companies which tick most of the boxes for investors but still find themselves hamstrung by inclement socio-political environments which have thrown their home economies into a state of funk. Despite such companies enjoying market leadership positions and strong return ratios, the growth of such companies in recent years has been feeble at best and indifferent at worst. The best such stocks could do for investors is to be good mean-reversion-trades within a broader protracted bear market from time to time.

“Fine-Timing” Value

The best time then to be invested in a traditional value stock is when the underlying company has figured out a way to stop shrinking and start growing again. That’s when you get the best bargains. The time between when the value stock goes unrecognized for its growth prospects for a long period of time and when it becomes well recognized or ‘found’ as a growth stock, is when the big money is made in value investing. Ultimately every ‘value’ stock will begin to look like a ‘growth’ stock, once growth comes back, even if such growth is cyclical and may not last for several years. Think hard commodities, industrial chemicals, petrochemicals, energy and property to be obvious choices here.

Opportunities exist in every market. Turning over every rock or many rocks will eventually lead investors to ferret out the real gems. Easier said than done surely, as value traps could spring nasty surprises. Value is cheaper today than at possibly any time in memory and this is not coming from only the potentially “broken” price-to-book ratio nor is it due to a bunch of monopolistic companies. Rather, it is a pervasive phenomenon. Investors are simply paying way more than usual for the stocks they love versus the ones they don’t and this is mostly limited to a few sectors.

Value investors are justifiably experiencing excruciating pain. We could see new highs in the value spread from here. Could systematic value come back very quickly over say a few months or a year? We don’t know. Good investing isn’t about sure things and definitely not about precise timing, but by having the odds in your favour by a significant amount.

To conclude, looking at where we are and from where we’ve come, it wouldn’t be wrong to believe that value in some shape or form will begin to find favour, if not widely, then in certain discernible pockets of the world and sectors as we emerge from the pandemic. It would be a slow and inexorable climb, but it feels to us that earlier this year, the nadir of this multi-year trend has been plumbed.

APPENDIX

What Style/s have worked

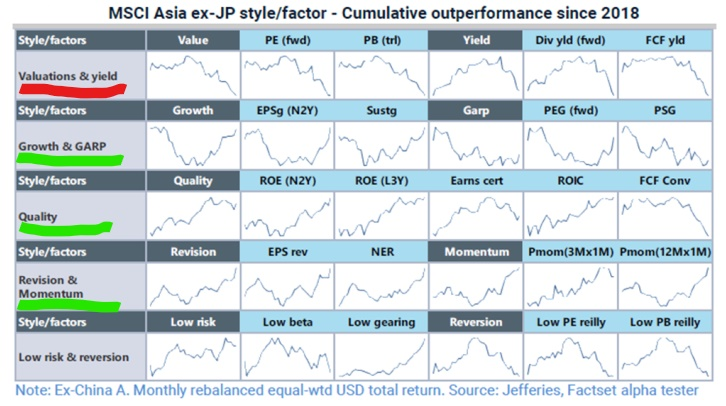

The following charts tell the tale eloquently enough.

- “Valuation and Yield” as a style has been beaten by almost every other style/ factor of investing over the last two years.

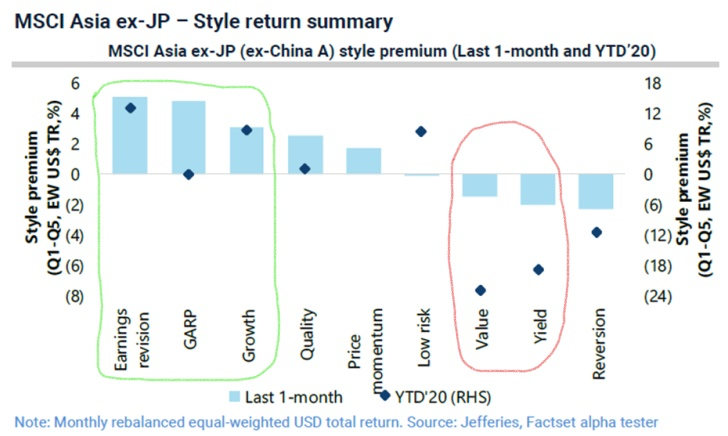

2. Earnings revisions, Growth at reasonable price and pure Growth have beaten Value and Yield strategies by some distance in Asia ex-Japan…

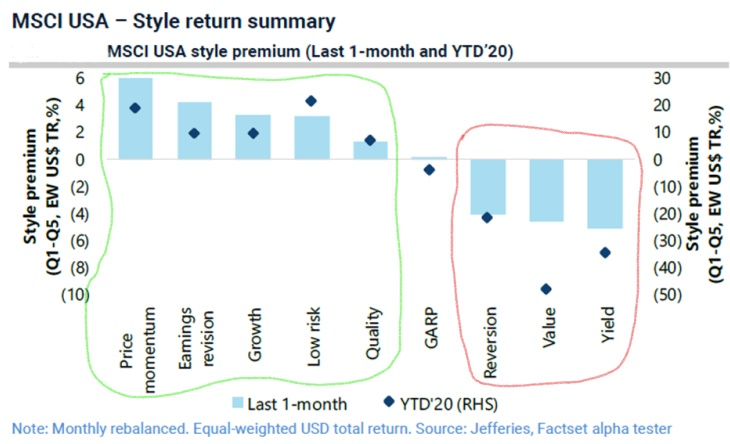

3. …and in the U.S. as well

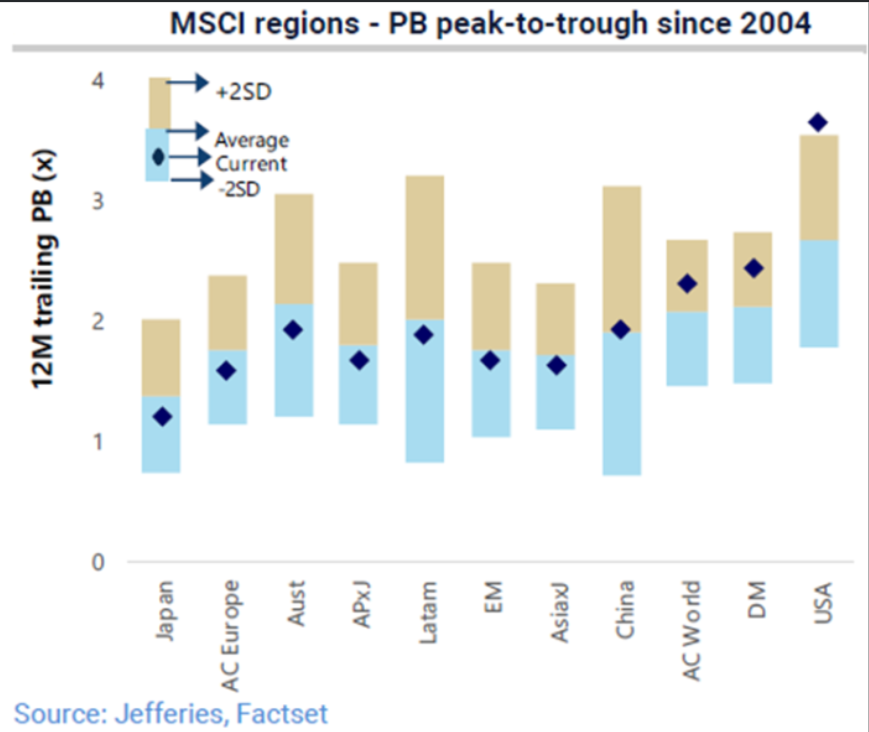

Where is Value to be found?

If we just use Price to Book as a metric for the sake of simplicity, the results are pretty obvious. Barring the U.S. and a handful of markets, value abounds across the globe.

- Anywhere on the planet except the U.S. and parts of the developed world.

2. There is plenty in Asia ex-Japan, except Taiwan and to some extent China and India

End

Disclaimer

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither its accuracy and completeness, nor the opinions based thereon are guaranteed. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This information is directed at accredited investors and institutional investors only.