Two abnormal months have showcased the value of not taking things for granted, as life brings new and unexpected perspectives every day. The coronavirus health crisis has not only morphed into an economic shock but also changed social behaviour – how family, friends, colleagues and competitors interact with each other. A majority of the 7.8bn homo sapiens on planet Earth have been cooped up indoors, restricted from going out and meeting each other, some due to compulsion, others following guidelines and many due to fear of a small unknown inert organism called the SARS-CoV-2/ COVID-19 virus. Birthdays and weddings, occasions for people to get together and celebrate, are being held virtually over the innumerable online communication tools – Zoom, Skype, WebEx, Hangouts, etc. It is amazing how quickly human beings adapt to different environments.

Investors, licking wounds from the first quarter, are eagerly trying to figure out future winners in this changing world. It is easy to jump onto the only winners that are visible in a Work From Home (WFH) framework – telecommunications and healthcare, but whether they bring sustainable change or people revert to old habits will depend a lot on the length of the current environment we are in. In the meantime, markets have been on their own course, defying many pundits, both bulls and bears. As we mentioned in last month’s newsletter Life after Armageddon, while markets wait to fathom the new normal, volatility will be the new norm. With time and the emergence of data, new patterns would get established and from these will emerge new winners and losers. The COVID-19 crisis is driving a battering ram into widely accepted notions of developed and developing economies, advanced and emerging societies. This month we look at the early indicators of how various countries have handled this unforeseen crisis to establish whether we can identify patterns that could point us towards new winners and raise red flags on the laggards. This is not a race to the finish line as the exit from the coronavirus mayhem is going to take a long time, but in the meanwhile it would be useful to avoid being the hare who sprints early but falls by the wayside of the long and gruelling trudge before us.

The Global Impact

The coronavirus crisis has brought economic activity in every part of the world to a grinding halt. Investors who are used to fathoming economic trends in a country by poring over statistics are facing new challenges. Years of globalisation and supply chain optimizations have made it difficult for statistics to fully reflect the local impact of shutdowns in any one country as the ripple effect of external demand collapse at the same time as disappearance of local activity makes it tough to strip out local trends from global knock-on effects in economic datapoints. Technology provides an answer to this conundrum. The ubiquitous mobile phone which sits in every pocket also provides a treasure trove of data. This raises the hackles of privacy advocates but, in the right hands, this data can provide insights that benefit the whole of society.

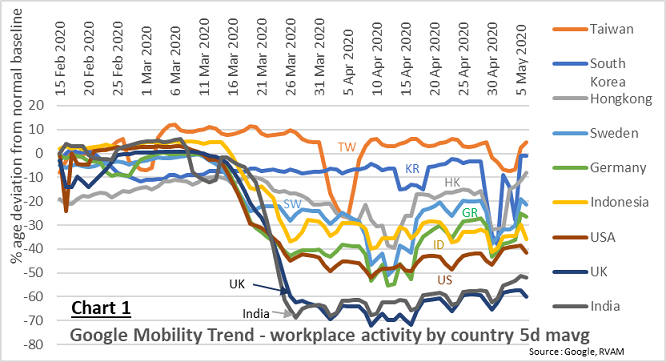

Google is using data gathered from mobile devices to provide aggregated, anonymized insights to help authorities make critical decisions to combat COVID-19. These Community Mobility Reports are available on its website to anybody who wants to understand activity trends across different categories of places such as parks, transit stations, workplaces, residences, etc. The data compares daily activity in each of these locations to the average base level of activity observed over a month in January 2020, i.e. before the coronavirus changed everybody’s behaviour. We analysed data for workplace activity in various countries to try to figure out how different countries are faring in these tough times. The crowded chart alongside shows the aggregated output of trends across various countries.

Anecdotally, the fact that Asia – especially North Asia – has managed to weather this crisis better is well known, but a cursory glance at the chart above will shock most observers at the divergence in trends between developed Asian countries and places like the U.S. and the U.K. which have decimated their economies in the process of trying to contain this pandemic.

What the chart shows is a moving average (5 day) of observed daily activity in every country. We used a moving average to smooth out the spikes seen over weekends/ holidays in different countries. The spectrum of countries chosen gives a broad understanding of global trends and also helps us understand best practices and lessons that could help countries emerge from their current state of limbo.

Taiwan clearly stands out by the fact that they have gone through the whole phase without losing any man-days of activity over the last three months when the virus was wreaking havoc across the straits in mainland China as well as the wider world. They went through every event that impacted other Asian countries – people entering from China, regional travel, second wave of students returning from the West testing positive for COVID-19 – but came out unscathed economically. South Korea on the other hand, despite taking early precautions, had a spike from a rogue local cluster, but quickly managed to put in place an aggressive regime of testing, isolation and workplace precautions without an undue burden on economic activity. The fruits are visible from the fact that workplace activity continued at a steady -10% rate and recovered back to normal by early May when another cluster hit them. The clear lesson from each of these examples is to tackle the crisis aggressively, early and with strict distancing measures which are socially adhered to by the wider population.

The Western Shock

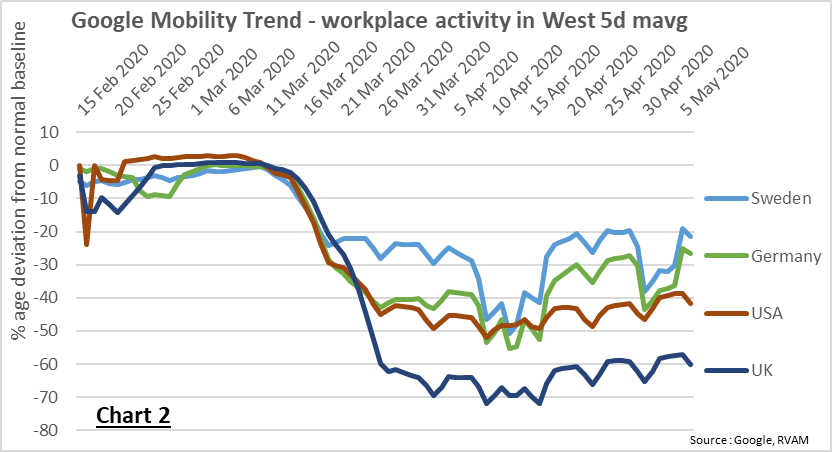

While the two developed Asian economies managed to contain the fallout, what is shocking to many observers is the near decimation of activity taking place in the Western world as authorities struggle to come to grips with this emerging situation. The early days of March were like a tsunami which hit every part of the world and we can gather that by looking at the steepness of decline seen in the graph on the previous page for every country. The interesting story is the divergence over subsequent days and weeks as some countries seem to have got a better grip of the situation versus others.

In the chart alongside, we compare trends in four Western economies, each going through a different journey in terms of tackling this crisis. Sweden is the flag bearer of the voluntary social distancing theory in practice, while Germany, after initial stumbles, went the aggressive route of ramping up testing and isolation akin to South Korea. The U.K. and the U.S. on the other hand stumbled between politics, liberal ideals of human freedom and the harsh reality of an overwhelmed healthcare system, before clamping down aggressively on all forms of human activity and movement. Each of the routes has taken a different toll as the stark choice between human lives and livelihood (dependent on economic activity) has resulted in sub-optimal solutions.

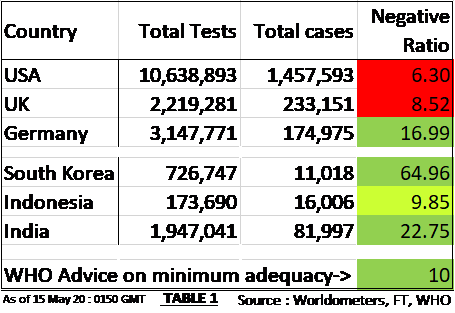

While many observers have tried to debate the merits of the Swedish model of self-enforced lockdowns versus mandatory social distancing in other Western economies, to date the economic impact between Sweden and Germany looks remarkably similar but with higher fatality rates in Sweden. From an economic perspective what is hard to imagine is that the global economy escapes without major damage when three of the five largest economies in the world (part of Chart 2 above) are seeing activity at such abysmal levels. The U.K. and the U.S. are still struggling to ramp up capacity in their healthcare systems to bring testing to minimum required levels (see Table 1 below). Till the healthcare systems are ready to confidently handle the risk of recurring surges in cases, it is difficult to imagine confidence returning for activity to normalize to baseline levels, as observed in North Asian economies.

The Testing Challenge

The WHO has consistently maintained that the key to getting this pandemic under control is testing and more testing. Large economies which have emerged faster out of lockdown had aggressively ramped up testing, like South Korea and Germany.

What is an adequate level of testing?

The WHO advice to consider a system to be doing enough testing to be able to pick up all cases is when there are at least ten negative tests for every positive case, which we have defined as Negative Ratio in Table 1 alongside. A benchmark number of 10 or higher indicates adequate testing.

Among Western economies, Germany has clearly delivered on this which has given them confidence to restart activity. On the other hand, the U.K. and the U.S. are still struggling to ramp up testing to levels where authorities are confident that they will be able to identify all the COVID-19 cases floating around in the population. They will get there eventually but till that time it is reasonable to expect activity levels to remain subdued.

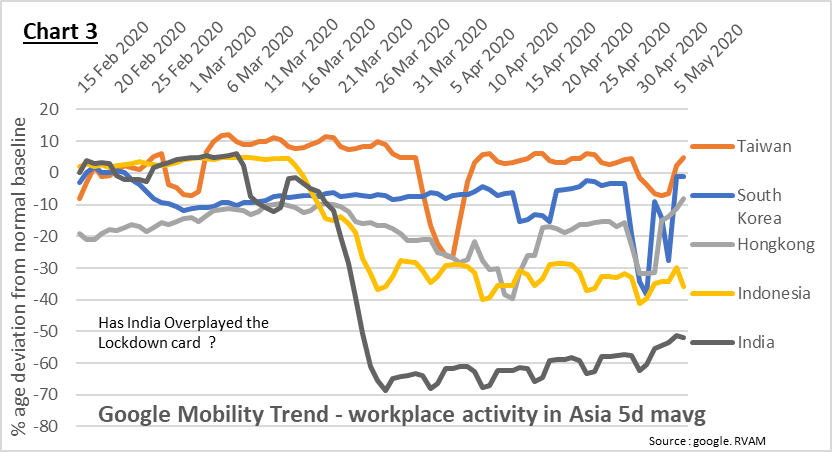

The Asian Divergence

As Western economies try to find their way out of this crisis, it is instructive to compare the Asian economies and try to gather insights from countries which have managed this crisis better without having to make the stark choice between life and livelihood. Chart 3 alongside compares activity trends for North Asian countries with those of the large South Asian economies.

Both Taiwan and South Korea have managed to get their economies back to normal levels with strict workplace protocols. Hong Kong which, after its second wave, put in strict measures, is seeing activity slowly creeping back to normal as the virus spread comes under control. The populous economies of India and Indonesia seem to be in the early stage of managing the COVID-19 crisis, with cases continuing to rise but at a measured pace. What is starkly different is the level of activity-hit which India is going through when compared to Indonesia, though in terms of the epidemic, the per capita spread seems similar at this point, while India seems to have a better grip on both testing and fatality levels when compared to Indonesia. Table 1 above shows that while Indonesia has just about managed a reasonable testing level, India has been testing at levels which are better than Germany. The high Negative Ratio indicates one of two facts: either the epidemic is not as widespread or the infrastructure is robust enough to be able to handle cases being thrown at the system. Both these scenarios do not justify the kind of complete lockdown that India is currently experiencing. India should theoretically be following the path of either South Korea or Germany and allow activity with adequate social distancing measures. Instead, the measures taken seem as draconian as those enacted in the U.K. where the system has got swamped by cases way above system capacity with a government struggling to deliver adequate testing but consistently missing deadlines.

One of the questions for posterity to answer is whether India followed its past colonial master, the U.K., blindly into a harsh lockdown (Chart 1) despite not having a statistically significant number of cases in early March. Are decision makers (bureaucrats and politicians) too attuned to taking cues from the West, ignoring best practices which may have developed towards its east, among Asian countries.

The Emerging Asian Giants

As we ponder a post-coronavirus world, we need to think about where the three emerging giants – China, India and Indonesia – stand. One thing is obvious: over the medium term, China needs to be considered on its own, in isolation, given the very different approach and containment strategy it has adopted, which has entrenched a system that is very different from the rest of the world. Economically, the managed domestic system stability will be played off against the expected global demand backlash (both direct and indirect). The potential shift towards an increasingly inward-focussed world plays into the natural strengths of the command and control mandarins in Beijing. From an investment perspective, this is likely to throw up new domestically-focussed opportunities.

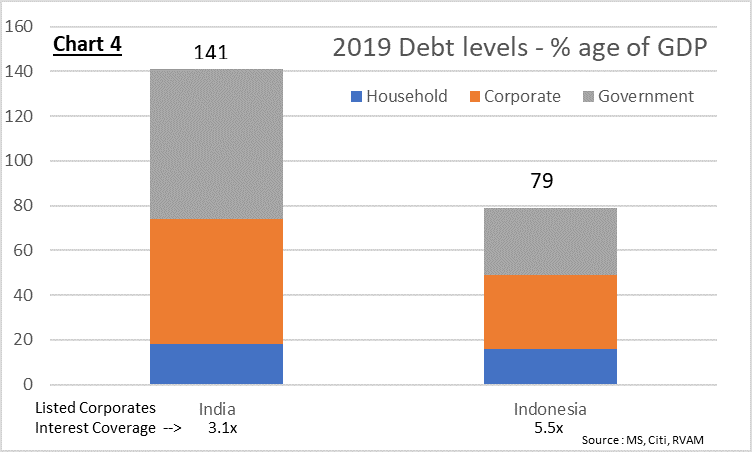

India and Indonesia till recently were moving on similar growth paths, something we commented on in our August 2018 newsletter. But the dramatically different impact the COVID-19 crisis is having on each makes one ponder the potential for their outlooks to diverge going forward. India went into this crisis on a weaker footing with a higher debt load than Indonesia, though with seemingly higher growth potential. The race for growth left corporate India with one of the worst interest coverage ratios (3.1x) in Asia with high debt levels. On the other hand, Indonesia has leverage which is nearly half, and the listed corporate sector has a comfortable coverage ratio of 5.5x.

Chart 4 alongside compares the debt burden in these economies. While household leverage is similar, the significantly higher debt burden of the corporate sector and government in India could become a constraint for rapid recovery, especially given the expected dramatic downdraft in economic activity telegraphed by collapse in activity as shown in Chart 3.

The systemic economic shock from shutdowns is going to increase the debt burden of both government and corporate sector over the next few months in every economy around the world. Into this backdrop steps the banking system, which becomes critical for economic recovery and there lies the biggest weak link for India.

Coming into this crisis, the biggest weak link for India when compared to other Asian countries including Indonesia was its fragile banking system. On an aggregate basis the system is undercapitalized with high non-performing loans (7% in 2019), rising credit costs (180bp in 2019) with low profitability (8% ROE). The collapse in economic activity over the last two months is only going to worsen this situation. In contrast, Indonesia has a robust banking system – well capitalized, earning 15% ROE with low NPL (2.1% in 2019), with stable credit costs (110bp) with significant cushion to absorb any shock from the coronavirus crisis.

When comparing economies in Asia, many investors point out to leverage in China and its banking system. While its aggregate Debt to GDP at 275% is higher than in either India or Indonesia, its repressed and tightly managed system ensures that the banks are reasonably capitalized and earn enough to manage the systemic risk from the corporate sector, which till recently had a very healthy interest coverage ratio of 6.6x.

The Outlook

It is always difficult in the midst of a crisis to forecast the path to recovery, especially when we are faced with a pandemic that is still not well understood by healthcare professionals. But there are enough examples of countries managing to get back to normal and this gives us confidence that there is a path to recovery which is not onerous. It requires focus to put in the right enabling environment. Some countries already have them in place, others are getting there and will learn from peers. But the hara-kiri being committed by India is something which may prove very costly and that worries us. A fragile financial system jumping headlong into a lockdown which at this point may not be needed, requires us to think hard and fast and change track before permanent economic damage is sustained. The current path of India concerns us. We would rather go for the slow tortoise Indonesia, which seems stable and robust, rather than chase the allure of a fast-growing India, which may be hurling towards a crisis at breakneck speed if not arrested soon.

End

Disclaimer

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither its accuracy and completeness, nor the opinions based thereon are guaranteed. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This information is directed at accredited investors and institutional investors only.